The biennial Grassroots Justice Prize competition recognizes grassroots organizations and institutions, large and small, across the globe, that are working to put the power of law in people’s hands. The Grassroots Justice Prize is brought to you by the Global Legal Empowerment Network in collaboration with Namati, The Elders, Walk Together, UNDP, and World Justice Project. Nearly 200 organizations from around the world applied for the three awards offered under this year’s competition. From India to Togo to Colombia, they are tackling some of the greatest injustices of our time by helping people to know, use, and shape the law.

Kav LaOved (KLO) is the 2017 Grassroots Justice Prize winner in the #WalkTogether Prize for Courage category. They received about 2,600 votes supporting their nomination.

Kav LaOved is an Israeli organization committed to the defence of workers’ rights and the enforcement of Israeli labor law, designed to protect every worker in Israel, irrespective of nationality, religion, gender and legal status. KLO aspires to prevent abuse and exploitation of workers by demanding fair employment terms and conditions, addressing both individual cases and the systemic violations of workers’ rights. To fulfill those goals, KLO runs public education campaigns to raise awareness of workers’ rights through research, reports, workshops, flyers, and lectures to workers, lawyers, officials, and other stakeholders. The organization also provides individual assistance to workers in person, over the internet, via a telephone hotline, and on field visits.

To learn more about the organization’s history and progress, and to celebrate their work, we interviewed Eliahu Abram, Kav LaOved board member and senior human rights lawyer.

Q. How did Kav LaOved’s work begin, and why did the founders decide to focus on the defense of migrant workers?

A. The organization was founded to protect labour rights of Palestinian workers who entered Israel, crossing the green line from Gaza Strip and the West Bank, in the beginning of the 1990s at the time of the First Intifada. The founders were volunteers who were disturbed by the denial of rights of these workers who were not enfranchised under the Israeli system, who were not getting full protection by any means from the Israel Labour Federation and who were easily exploited as day wage workers. Then we started to work with migrant workers from other countries, because many restrictions were placed on Palestinian workers from the territories for security reasons and they were frequently replaced by foreign workers who came in as migrants. The position of these migrant workers was similar to the original Palestinians that the organization defended.

The founders were complete civilians, they weren’t lawyers, they weren’t professionals, they were just people who couldn’t stand the injustice that they saw before their eyes and they managed to create an organization out of nothing.

Q. The organization works with one of the most vulnerable groups in society: migrants and asylum seekers. What are the main challenges KLO has faced?

A. One of the main challenges surprisingly is enforcement. Israel has a very excellent system of labour laws. It can be improved but it’s certainly a set of laws that advance the rights of workers and give power to collective agreements. The problem is that the bodies that are supposed to enforce these rights are underfunded, there are very few people who can go out and actually check

whether the rights are being violated by employers. It’s difficult to get the government agencies to enforce the laws that they are supposed to enforce particularly on behalf of those who are viewed as outsiders as strangers, above all the asylum seekers who arrived in Israel in the past 12 years and are viewed by many as infiltrators, as people who shouldn’t be here.

Another challenge which might be more particular to Israel than other countries is the relationship between security and labour rights. The public and the government agencies frequently view security as the issue that justifies creating many difficulties for these workers, whether the Palestinians that enter Israel to realize their rights that they are entitled to under law and these asylum seekers, to have any kind of legal employment. Asylum seekers in Israel are frequently portrayed as infiltrators, because many of them cross the border illegally from Egypt, fleeing persecution in Sudan and Eritrea.

Finally, one challenge related with our organization is funding. We operate mainly with the help of volunteers, but there has to be professional staff, there has to be office space, there has to be professional legal guidance. These aspects of the organization cost money and it’s very difficult to get funding for our core tasks.

Q. What are the risks associated with the work KLO does?

A. I would describe the risks on 3 different levels:

One is the risk of violent confrontation. This is the case particularly in our work with agricultural workers. As part of our fieldwork, representatives of our organization come to the farm or the agricultural site where the foreign workers, most of them from Thailand, are employed and to meet with them. We don’t tell the employer in advance that we are coming in order to avoid efforts to prevent us from coming and hearing complaints.

We come and we meet the workers in their residences. They pay rent for where they live so it ought to be their right to welcome whoever they want where they live. However the agricultural owners view those who enter as trespassers and not infrequently our team is confronted by shouting, anger, sometimes threats, sometimes even real threats of a shooting. That’s one level of threat. Of course, those who are even more threatened are workers themselves, not our staff, we arrive and leave, but workers remain and they can be threatened with a dismissal.

Another level of threat is organizational. When we publish criticisms of employers and employant organizations, they are often very well funded and they have professional legal teams, and they threaten our organization with libel suits for vast amounts of money which would cripple the organization. They believe that in this way they can prevent us from revealing their violations of law and abuses of human rights. It can create an intimidating atmosphere.

Finally, the third level of danger that we face related to a spirit of intolerance and xenophobia which is directed mainly against foreigners, the foreign workers and particularly asylum seekers, but it rubs off at those who represent them. There’s a segment of society who view these outsiders who are working in Israel as a threat, as a dangerous people who should not be there and those who defend them as those who are attacking somehow the security of the country. So far this hasn’t led to personal violence but it’s an atmosphere which makes work difficult.

Q. How does the organization deal with those risks?

A. The first tactic is to simply meet the workers in a way that doesn’t attract attention, in a hidden place. Where there is a real threat of violence our staff simply leaves, leaving information with the workers, how they can get in touch or they can call to come back another day.

With respect to the libel suits which at certain points became a real problem we simply stood our ground, we called their bluff, we knew we had true information, we knew we were reporting well-researched facts and we didn’t back down.

Q. The strategies and tools that the organization uses are complex and diverse, from helping workers understand and use law to strategic litigation to research and advocacy for policy change. How do your policy and litigation efforts work hand-in-hand with your direct assistance to workers in need?

A. Kav LaOved is an organization which lives and breathes its direct work with workers, its direct intake of complaints. In some cases, we go to sites and do fieldwork, but in general we have offices, and it’s incredible to come to our offices and see dozens of asylum seekers one day, domestic workers another day, caregivers another day. Many dozens come to our office to ask for assistance and information. This is how our organization acquires the data which makes it possible for us to influence policy and carry out meaningful litigation.

With respect to policy, what has happened is that the Kav LaOved is recognizednot only by the press but also by the legislative bodies, the Knesset committees (unicameral national legislature of Israel), and even by certain government agencies as the most reliable source for information concerning the communities we work with, in particular the tens of thousands of foreign caregivers in this country, and also concerning accidents at construction sites which are a grave problem in Israel, affecting mainly foreign workers and Palestinian workers.

The fact that we have this information from the individual complaints makes it possible for us to come to the Knesset and reliably report what the problems are and makes it possible for us to publish reports on particular issues.

Finally, our litigation stems entirely out of the problems that we discover in meeting the workers, whether it’s lack of healthcare or a form of employment which makes it impossible for the worker to change employers. These issues we discovered, we documented, and we bring them before the courts. I think our organization is an example of a kind of paragon of how direct assistance can lead to policy and legal changes.

Q. The ILO estimates that there are roughly 150 million migrant workers in the world today, making labor migration one of the planet’s most urgent justice challenges. In your experience, how does legal empowerment for migrant workers help to address this problem?

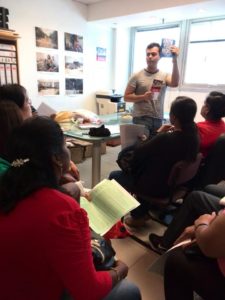

A. The position of foreign workers in our country, I suspect it’s similar in other countries, is very precarious, they come, they have no support community, nowhere to go if they should be dismissed by their employer. They don’t know the language, they don’t know where to turn in case of a serious complaint of any kind, they are completely vulnerable. This is why the first step is to educate, to bring information to these groups of foreign workers. We put together pamphlets which describe labour rights, give information of where a person can turn, they are translated to the relevant languages and distributed. We also have kind of education seminars where labour rights are explained to the relevant groups.

The ways in which this empowerment is changing the labour situation is first of all it affects the conditions of these former labourers. For example housing. We publicised terrible housing conditions in many of the agricultural farms where Thai workers were being employed. Giving publicity led to significant changes, led to publishing government regulations which set for minimum standards of housing. When employers have to meet humane standards for the foreign worker I think it protects the entire workforce.

Q. What are the main organizational successes and outcomes for which you feel most proud?

A. One is the elimination of limitations on where a worker can be employed. When a foreign worker comes and is told that he can only be employed by a specific individual, that his visa to be in Israel is limited to being employed in a specific household or by this a single employer, it’s a form of migrant slavery. We have brought this to the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court used that term of modern slavery and completely condemned this form of limitation.

Another is that in Israel, we have a very good system of national health care, but it was not being made available to foreign workers, even those who were here for many many years. We brought a case and after a struggle of many years, the Supreme Court held that longtime caregivers, longtime foreign workers who were here for an extended period of time must be entitled to government health care. This made a tremendous difference for the well being of a very large group of foreign workers in Israel.

Q. Why is the Grassroots Justice Prize important for your organization and how will it improve your work?

A. First of all getting an international prize was a great surprise and a great boost to how we feel about what we are doing. You work, you feel alone, it can be a lonely battle even if you are working with a group of ten people or twelve people – it’s you against a very unresponsive world and all of a sudden you discover that somebody else out there has recognised what you are doing. It gives a boost, it gives you greater power to continue doing what you are doing and therefore we are very grateful for this surprising award. Also I think the fact that it was awarded under the category of courage made us look at ourselves and say well that we didn’t realize that we are courageous. Aside from the subjective benefits of receiving such a prize and honour, we hope to translate this international recognition into political leverage. It will give us a better position to advocate on behalf of workers rights, certainly with respect to foreign agencies, foreign governments, the United Nations and international bodies. Now we can say we have international recognition so take us seriously. We are not just a small NGO, we are an NGO that someone out there in the world thinks is important. And finally there’s the mundane but important aspect that the prize money is important for an organization such as ours with limited funding and vast needs. We will use the prize money to further our work and we need it.

Q. As you know, this prize is an initiative of the Global Legal Empowerment Network. How does the network help to support your work? In what kind of activities/initiatives would you like to be involved in the future?

A. The Network in itself is a benefit, I think it’s important to be in connection with other organizations that work with similar issues, similar challenges, certainly as you mentioned international labour migration is a worldwide phenomenon and many similar challenges are being met by different countries. I think also from what I read in the news that the hostility of part of the Israeli public to asylum seekers is a problem that exists in many other countries, both in Europe and other places in the world. We can learn from the connection and the network between organizations.

I think that our workers and our volunteers could really benefit from participating in workshops that are established by your Network and meet other people who are doing similar work, find out how workers are empowered in other countries, what ideas other organizations and workers have carried out and we could certainly learn, and we might be able to impart from our knowledge to workers in other organizations and other parts of the world. It gives a good feeling to be part of something larger than yourself, larger than your regular horizons.