Stories

Twenty-Nine Years Without an Identity

The pickpocketer was fast. In the blink of an eye, Mahmoud’s wallet was gone. He lost the cash that was in it, his driving license and—worst of all—his identity card.

Without an ID card in Kenya, you cannot vote. You cannot open a bank account or get a loan. You cannot gain admission to school or get a job. As Mahmoud explains it, “Without an ID it’s like you have no life, you have completely nothing.”

Replacing his ID card was a matter of particular urgency for Mahmoud. He was a lorry driver. In order to work, he needed his driving license, and to replace it, he needed an ID. He went to the police station and reported the incident. With the necessary police form in-hand detailing the loss of his ID and license, he headed to the District Commissioner’s office.

Mahmoud provided the District Commissioner’s registrar with the form and his ID number, which he had memorized. But there was an issue: the records revealed two people were registered to the same ID number. This raised suspicion, particularly because of his ethnicity.

Mahmoud is a member of Kenya’s predominantly Muslim Nubian community. Despite having citizenship under the law, Kenyans of Nubian heritage face discrimination when applying for identity documents. “The other ones when they go, they are not asked for all these other documents like we are asked,” explains Mahmoud. “But if you are Muslim or a Nubian, that’s when all kinds of questions come flying.”

The registrar sent Mahmoud to the National Registration Bureau where he was fingerprinted. His prints were shown to be in the system and associated with his ID number. He also provided them a bank account form he had that had his name and ID number on it. Still, they would not issue him a new ID.

Mahmoud lost his job. Without proof of his citizenship, he was unable to find work. “I really struggled. I couldn’t even get manual jobs because of the lack of ID.” He had a wife and four young children at the time.

The family got by on the salary his wife made braiding hair at a salon while Mahmoud continued to try to resolve the issue.

This was the reality Mahmoud and his family faced for the next 29 years.

Mahmoud spent almost his entire adult life trying to navigate the complex administrative and legal systems. In 2014, he finally found the guidance he needed. The Nubian Rights Forum (NRF), a Namati partner, had started work in the Kibra area, where he lived.

NRF trains community paralegals to assist other members of their community with overcoming discrimination to obtain birth certificates, national ID cards, passports, and death certificates in accordance with established legal procedures. Mahmoud went to their office and told them about his predicament.

Hassan, one of NRF’s paralegals, took on the case. He worked closely with Mahmoud to help him understand and navigate the relevant laws and processes. Hassan explained to Mahmoud that as a member of the Nubian community, he would have to undergo “vetting” by a committee made up of elders and government officials as part of the identity document application process. The process would require him to answer extensive questions on his origins and submit documents such as the birth certificates of parents and grandparents— things not required of other ethnic groups in Kenya.

Hassan accompanied Mahmoud to the registration office to fill the appropriate forms to be booked for vetting and prepared him for what the process would entail.

Over a period of two years, Mahmoud was subjected to three vettings. The panels asked him for his father’s birth certificate and his father’s ID. They asked him for documents showing his ID number. They asked him about his father’s character and integrity. They were tough, says Mahmoud, “you can’t just escape their interrogation so easily.”

Hassan and Mahmoud continually followed up with the registrar, ensuring his forms were being processed.

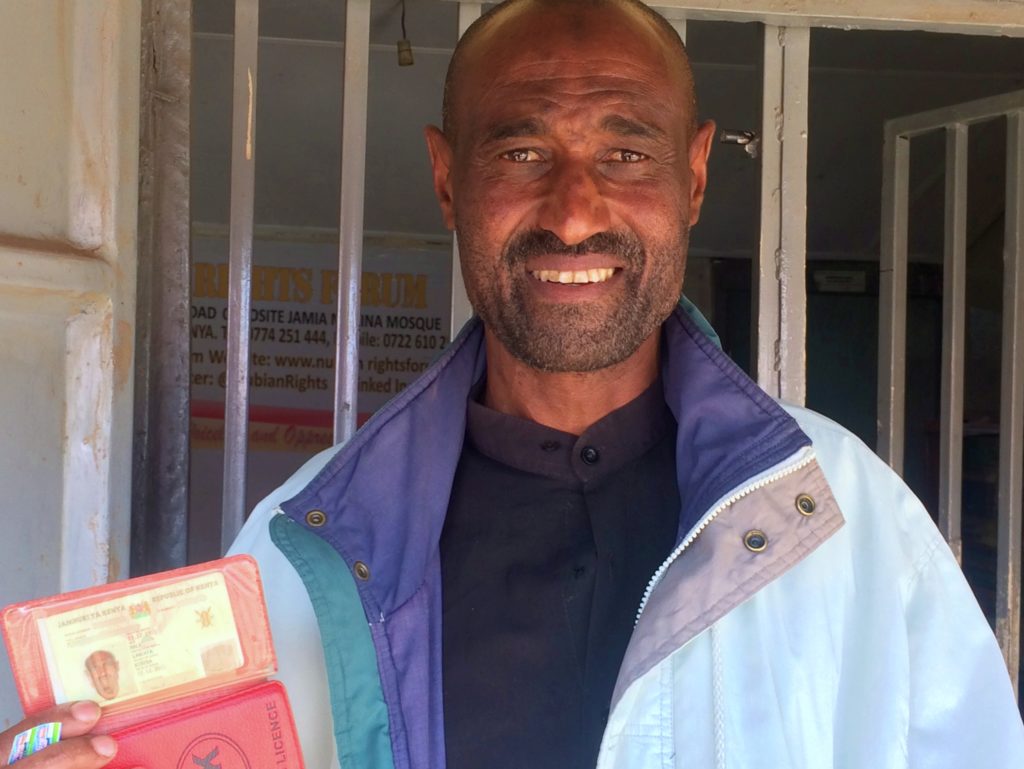

Finally, after 30 years of trying, Mahmoud was told he would be issued a new identity card.

The first thing Mahmoud did after picking up the long-awaited card was to run to the NRF office to make photocopies, storing one in NRF’s files. He then went to get a voter’s card, a party membership card and, of course, a driving license.

Mahmoud is now back behind the wheel of a lorry, earning a salary and supporting his family.

Mahmoud proudly displays his new identity card.