When a housing programme in the Indian state of Haryana guaranteed land to impoverished families in Raniyala, a village in Mewat district, it seemed like welcome news. Instead, government officials seized the land and refused to hear the villagers’ objections.

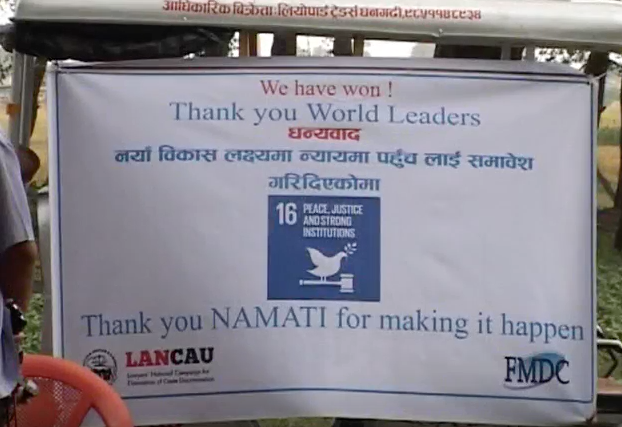

Could a newly agreed global framework support this community and others fighting injustice? Of the 17 global goals for sustainable development that come into effect on 1 January, goal 16 commits to “access to justice for all”.

The goal, which covers peace, justice and strong institutions, was contentious. Many governments said development should be a technical, economic undertaking, and that justice was too political to be included. The passage of goal 16 at the UN in September was therefore a milestone, a recognition that people cannot improve their lives without the power to exercise their rights.

But some countries are now taking the wind out of the goal by choosing a narrow set of indicators by which to measure progress.

At an October meeting in Bangkok, the expert group tasked with developing a monitoring framework for the new sustainable development agenda rushed through discussion of the 16th goal in what many viewed as an attempt to avoid public debate. Governments that had championed goal 16 at the UN general assembly just months earlier suddenly muted their support. The experts focused on what state agencies already measure, rather than what they could or should measure.

The draft indicators focus exclusively on criminal justice, including pre-trial detention times and crime reporting rates. Those numbers matter, but justice is bigger than police and prisons. Justice requires that every organ of the state treat citizens fairly.

If governments and the UN are serious about providing access to justice for all, global indicators must go beyond any one set of institutions. Measurement should instead focus on whether people faced with injustice are able to achieve a fair remedy.

In Raniyala, local women trained by the Haryana-based SM Sehgal Foundation supported community members to demand the return of land that was rightfully theirs. They formed collectives and gathered evidence, camping in government offices when refused a meeting. After five years, their efforts were rewarded. Seventy-six families now have decent homes.

The whole community has benefited from the legal skills learned by the female advocates along the way. The women mediate local disputes, monitor and demand better health and education services, and have trained more than 22,000 people in legal literacy. Raniyala is one town, but these women are part of a global movement of grassroots legal advocates who tackle injustice every day.

At the Bangkok meeting, the UK representative questioned the feasibility of measuring citizen perceptions of justice, a concern quickly echoed around the room. Yet it was the UK that pioneered a citizen-focused approach with the Paths to Justice survey that has been used to shape policy since 1996. Today, the World Justice project collects data on how people interact with the law in more than 100 countries.

Drawing on that experience, we support two global indicators. The first (pdf) focuses on the proportion of people, from all those who faced an injustice in the past year, who tried to resolve it using any institutional channel – the courts, but also administrative and customary institutions – and felt the outcome was just. The second asks how many citizens can access independent legal support that they find helpful.

These two indicators would anchor goal 16 in real experiences. The first focuses on how injustices are resolved. The second challenges governments to give legal empowerment efforts – the work of the advocates in Raniyala and their counterparts around the world – the space, recognition and even some of the financing that they need, while respecting their independence.

We know that justice requires not just investment in state institutions but organisation and engagement by the people themselves. It is empowered citizens that create responsive governments.

What if we lose this battle? Amartya Sen told heads of state in September that reducing goal 16 to anaemic indicators “is like trying to cancel the French Revolution because liberté, égalité and fraternité couldn’t be precisely measured”. The global movement for justice, which made goal 16 a reality in the first place, is greater than any set of metrics.

Already, civil society groups in Kenya and the Philippines have used goal 16 to press for progressive changes: a legal aid bill in Kenya, and a section on access to justice in the Philippines’ national development plan. And each country will choose national indicators to complement the global ones.

Goal 16 belongs to the people, and the people won’t relinquish it easily.

Vivek Maru is Namati’s founder and CEO. Stacey Cram is Namati’s Global Advocacy Specialist. This OpEd first appeared in The Guardian.