Deciding whether or not to allow an investor to use community lands and natural resources is one of the most important decisions a community can make. Namati and the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment (CCSI) have published two new guides to help communities prepare for interactions with investors and, if they so wish, negotiate fair, equitable contracts. These guides are the first of their kind. In this blog, Namati’s Rachael Knight and CCSI’s Kaitlin Cordes describe why and how these guides came to be.

Rachael Knight:

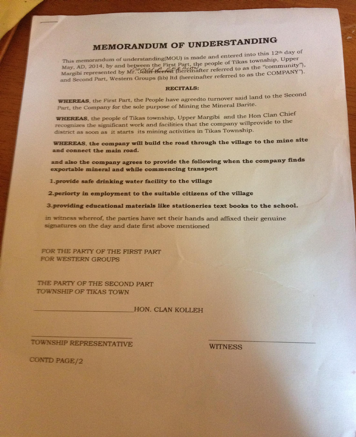

In 2014, I was in Liberia working with the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI). One day, SDI’s Director, Silas Siakor, showed me a scan of a crude, one-page memorandum of understanding (MOU) that an investor from Monrovia had given to a community to sign.

A crude MOU provided to a Liberian community by a national investor

The contract, asserted simply that “Whereas, the First Part, the people, have agreed to turnover said land to the Second Part, the company, for the purpose of Mining the mineral Barite.” The boundaries and definition of this “said land” was not specified. In return for this unknown piece of land, the company promised to “Build the road through the village to the mine site…provide safe drinking water facility to the village, periority [sic] in empowerment to the citizens of the village, providing educational materials like stationeries text books to the school.”

The community had, quite wisely, not signed it, and immediately called SDI seeking their advice.

Later that year, SDI shared another MOU with me. This one was between the community of Dowein and a Liberian palm oil company. The company had convinced the community leaders to grant them “a minimum of 20,000 hectares” of land—an area larger than the entire chiefdom.

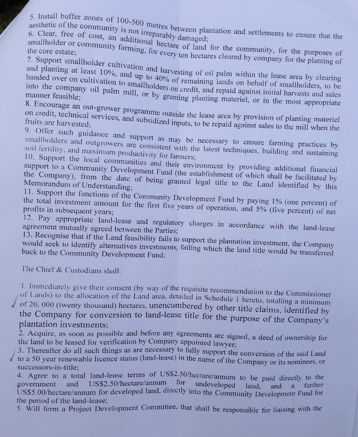

The MOU between Dowein community and a Liberian palm oil company.

The MOU did not specify the terms of the investment, the land to be granted, if the communities had rights to use and inhabit the land, or any concrete benefits that would be provided to the communities. Further, the MOU required that the signatories not disclose its content to “any third party unless required to do so by law” and to agree that the company would have “total exclusivity over the Land” for one year. SDI eventually supported the chiefdom to successfully contest the MOU.

These two contracts made a significant impression on me, and confirmed my suspicions that national elites were in the process of manipulating rural villagers into leasing or selling vast quantities of land to them on unjust terms, then getting them to “sign papers” to create a legal veneer over very shady transactions.

So much energy, globally, has gone into addressing large-scale land grabs by international investors—there have been innumerable conferences, working groups, commissions, reports, and regulatory frameworks, etc.—but no one seemed to be paying attention to all of the smaller, national-level companies who were grabbing thousands of hectares of community lands by extorting local power dynamics, then formalizing their thefts in crude contracts.

Often, these “investors” are powerful government officials, military leaders, politicians, or national elites who intimidate and bribe local leaders or make false promises of large payments or infrastructure projects they have no intention of fulfilling.

Community members are often eager to open their lands to investors, believing that they will bring jobs, much-needed roads and services, and otherwise lead to the development of their community. But, having worked with rural communities to protect their land rights for almost 20 years, I have seen some of these promised benefits: half-built schools, medical clinics with no beds, staff, medicines or supplies, decimated forests, polluted water sources, and few—if any—new jobs for community members.

I looked far and wide for low-literacy “how to negotiate with investors” guides that clearly explained how to respond to investors seeking community members’ signatures on inequitable, vague, and often bad faith contracts like these, but found none. Most of the resources I found were very legal, very technical, and written for lawyers.

So, I sat down to begin writing a guide for communities. However, I soon realized that my rudimentary understanding of contract law (enough to pass the bar exam!) was vastly insufficient; I needed to collaborate with contract law experts. So, I reached out to the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment (CCSI) to see if they would help.

Kaitlin Cordes:

CCSI has been working on contracts related to land deals for years, but our focus has mostly been on contracts signed between investors and governments for large parcels of land. We had seen a number of those contracts that seemed like terrible deals for governments and their citizens, so I was not surprised that the community-investor contracts that Rachael told me about were even worse.

After discussing the challenges that communities face when negotiating contracts with investors, my colleagues and I decided to partner with Namati on this project. Combining our respective experiences and expertise would allow us to tackle the issues more effectively than either organization could on its own.

Together, we decided to write “how to” guides that could help communities and their advocates both to prepare for interactions with potential investors and to negotiate better contracts if they do decide to welcome external investment.

We wanted to create resources that were accessible but legally nuanced; globally useful but practical within specific national contexts. They needed to support lawyers, paralegals, and community members alike.

This was much harder to do than it sounds. Contract law—and laws relevant to land rights and investments more generally—are complicated and differ widely by country. Making grand pronouncements and sweeping generalizations wouldn’t work, but neither would getting lost in the details of specific countries’ laws.

We tackled the project with enthusiasm. Rachael focused on advising communities on how to identify long-term priorities and a vision for their desired future, how to understand the value of their lands, and how to ensure the participation of all community members in decision-making. She also confronted challenges such as how to rein in corrupt leaders intent on signing deals that only benefit the community’s elites and how to help communities stay unified when investors use divide-and-conquer tactics.

Meanwhile, my CCSI colleagues and I focused on the details of what good contracts should and should not include.

We tracked down dozens of recent examples of contracts between communities and investors. As feared, they were generally atrocious, along the lines of what Rachael had seen in Liberia.

We included “red flag” language from those contracts in the guide to show community members the kind of slippery phrasing to look out for, phrases such as “to the best of the company’s abilities,” “in the manner the company deems fit,” and “the company will reasonably endeavor to…” that may ensure that the company is under no obligation to actually do what the community believes the investor is agreeing to do. We also proposed better, more protective legal language that communities could adapt to their contexts in order to create stronger enforceable rights.

It takes a village to do most things well, and these guides are no exception. We’ve workshopped them with civil society groups and paralegals in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Laos, and the United States. Their grassroots experiences and perspectives were invaluable. A number of legal experts also closely reviewed the guides, providing a different but equally invaluable perspective.

Rachael and Kaitlin:

If an investment project is carried out in a respectful and inclusive way, it may help community members to achieve their long-term goals. We hope that supporting communities to understand the advantages, disadvantages, and risks of investments, as well as helping them to push for fair, enforceable contracts, will increase the benefits and reduce the risks of investments. Empowering communities to engage with potential investors from a place of legal knowledge can improve contract negotiations, make it more likely that investments contribute to the community’s thriving, future, and increase the likelihood that the investment itself will flourish.