Post

Ground-Truthing the Environmental Impact of Development in India

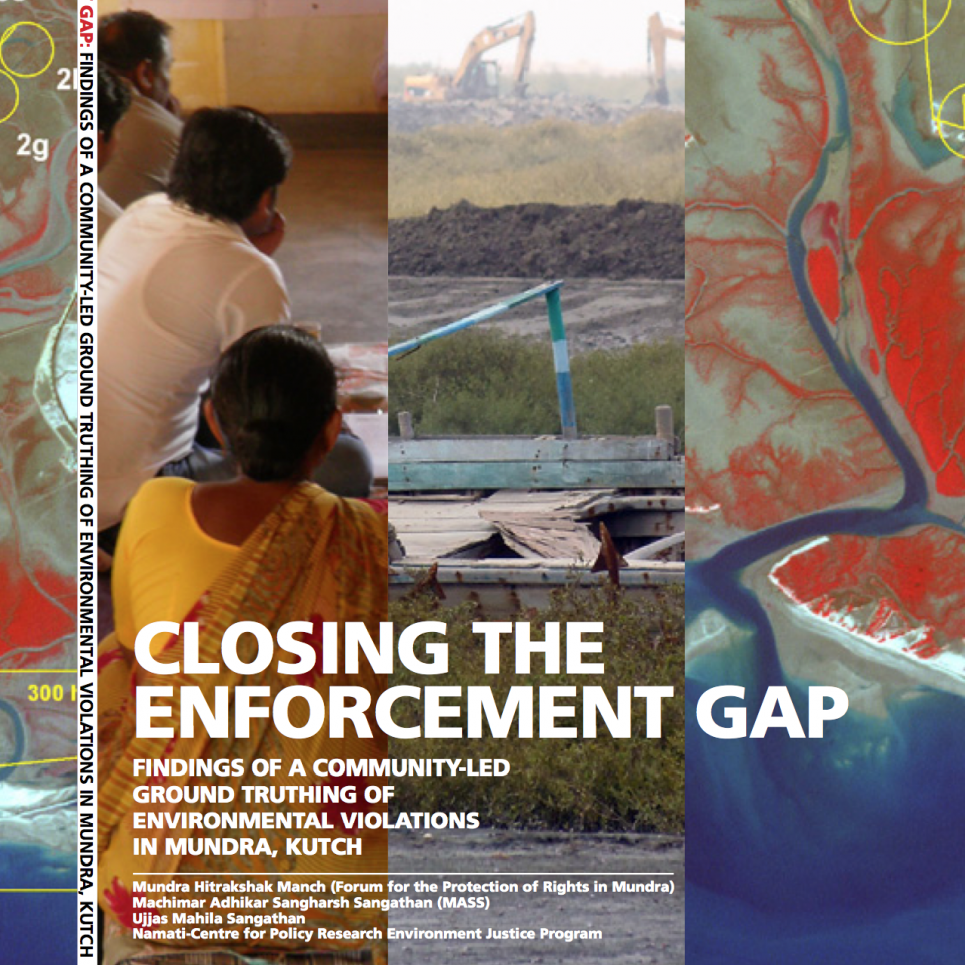

In the western Indian state of Gujarat is the large and austerely beautiful district known as Kutch. It is an ecologically unique place, with shallow wetlands, salt flats, important grasslands, and the channel-cut Mundra Coast. Mundra is known for its rich biodiversity, with a combination of inter-tidal mudflats, mangroves, and natural creeks supporting a rich diversity of seaweed, corals, fish and an array of marine life.

In the western Indian state of Gujarat is the large and austerely beautiful district known as Kutch. It is an ecologically unique place, with shallow wetlands, salt flats, important grasslands, and the channel-cut Mundra Coast. Mundra is known for its rich biodiversity, with a combination of inter-tidal mudflats, mangroves, and natural creeks supporting a rich diversity of seaweed, corals, fish and an array of marine life.

The Mundra belt has always been considered to be extremely ecologically fragile and economically productive. This network of creeks, estuaries and mudflats are unique and very important because fishermen use these to land their boats to keep them safe from strong winds and currents. The creeks also form a natural drainage system that, if disturbed, can lead to flooding during monsoons. While the region supports the livelihoods of fishing villages near the sea, the inland areas have several pastoralist and farming communities who rely on the availability of sweet water and vast stretches of common lands. Many people also rely on the coast for their salt panning work.

“Companies don’t talk to people. They are not ready to listen to us. Many locals think they will get jobs in these companies, but they don’t. Companies make false promises.”

-Husain Kara, Fisherman

Gujarat is also one of the first landfalls in India for shipping from Europe and the Middle East and the Mundra region has for the last decade and a half seen ferocious industrial expansion. A range of multi-purpose ports, coal-handling facilities and thermal power plants have all been granted approval and built. These approvals were granted under various environment regulations. This report from Namati, in partnership with Mundra Hitrakshak Manch (Forum for the Protection of Rights in Mundra), MASS and Ujjas Mahila Sangathan shows that the enforcement of these regulations has been woefully inadequate.

One of the largest of Mundra’s industrial and infrastructure projects is the waterfront development project (WFDP) known originally as the Mundra Port and Special Economic Zone and now known as Adani Port and SEZ. This project, which will eventually encompass 13,000 hectares – equivalent to roughly 13,000 rugby pitches – was given clearance by India’s Ministry of Environment and Forests under India’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) notifications on 12 January 2009.

Under EIA notifications, activities like mining, power generation and major industrial projects need to be preceded by a process of assessing potential environmental impacts and by a public hearing before permission can be granted to begin construction.

With every permission it issues, the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) sets conditions that need to be met during the construction and operation of the projects. The environmental clearance for the Adani Port and SEZ development was issued alongside 17 specific and 14 general mandatory conditions. These conditions have the power of law and restrict the kind of activities permitted in a specifically defined part of the coast.

Past experience has shown that both government enforcement of and corporate compliance with environmental regulations is often very inadequate. With this in mind, Namati and its partners undertook discussions among members of the communities in Mundra that had been affected by the waterfront development. We worked with village representatives, local activists, researchers, and community groups to explore the possibility of carrying out a community-led exercise investigating the compliance of the project with its environmental conditions. This would also ascertain the extent of enforcement of the coastal and environmental regulations related to the port project’s clearances. The report would measure the project’s impact on both people’s lives and the environment in the coastal areas.

Past experience has shown that both government enforcement of and corporate compliance with environmental regulations is often very inadequate. With this in mind, Namati and its partners undertook discussions among members of the communities in Mundra that had been affected by the waterfront development. We worked with village representatives, local activists, researchers, and community groups to explore the possibility of carrying out a community-led exercise investigating the compliance of the project with its environmental conditions. This would also ascertain the extent of enforcement of the coastal and environmental regulations related to the port project’s clearances. The report would measure the project’s impact on both people’s lives and the environment in the coastal areas.

The idea was to initiate a ground-truthing exercise. Ground-truthing is a term that has developed in cartography, meteorology and other sciences that combine image data with information on real features collected at a specific location.

Many of the issues the local community uncovered in its ground-truthing exercise – in particular the potential destruction of mangroves – had already been the subject of challenges before the project was constructed. After one case brought by fishermen, the MoEF even issued a legal notice to the developers asking them to explain why their clearance should not be revoked – yet the project had carried on.

“There is not enough grazing land for cattle. They used to drink water at the dam, but now the water is dirty. The rich are getting richer, the poor are getting poorer, and the rich are buying most of the available water. All the water in Kutch is going to companies, not villages.”

-Javjiba Jadeja, Baraya village

The ground-truthing report established that much of what locals feared has come to pass. Large areas along the sides of creeks have been cleared of their mangroves – which in turn is causing the destruction of the fragile ecosystem of the main and supporting creek systems in the area. Access for fishing communities to their fishing grounds has also been impeded. Despite conditions of the environmental clearance that are supposed to guarantee fishing vessel access, creeks have been filled in. Traditional pagadiya fishermen – who operate without boats and place their nets across creeks at low tide – were ignored in the clearances and their livelihoods have also been damaged.

The exercise also uncovered, through a right to information request, that only one copy of the supposedly mandatory six-monthly monitoring and compliance reports of the WFDP project were available.

For Namati, part of the purpose of this exercise was to try and achieve larger legal empowerment goals, in addition to uncovering the violations. Namati and its local partners attempted to create a process that both allowed local communities to gain a better understanding of the regulatory conditions and at the same time gather legally admissible evidence related to environmental violations. The importance of the ground-truthing approach is that communities themselves were able to correlate the social and environmental impacts of the development project with the enforcement and compliance processes of environment and coastal zone approvals.

Namati and its partners believe that is important to be able to draw lessons from the exercise so that it can be replicated elsewhere in India and so that it can help us prepare tools so that other communities can take similar actions in the future.

- Download the full report, Closing the Enforcement Gap: Findings of a Community-Led Ground Truthing of Environmental Violations in Mundra, Kutch, from the Namati publications page.