As per the information received in response to over 15 Right to Information (RTI) applications filed before the State CZMAs, all state governments except Goa have either issued orders or sent out letters to District Collectors for constituting DLCCs. These RTI responses were received between May and November 2014. However, even to date, DLCCs are yet to be constituted in many districts, leave alone be made functional.

In Gujarat an order was issued on 14 October 2013 directing the setting up of DLCCs. This order also laid down the powers and functions of DLCCs in Gujarat, which included powers to verify complaints, assist in enforcement and also take measures to protect the coast. The progress on constituting these bodies has been slow and low on priority in almost all districts of the state. As of early 2015, DLCCs had not been set up in 7 out of 14 coastal districts of the state.

Minutes of the meetings of Karnataka, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu SCZMAs accessed through RTI applications and from the respective SCZMA websites indicate that DLCCs are functional in these states.

Role

Even in states where DLCCs are already in place or where orders have been issued to set them up, there are huge variations in the role prescribed for these bodies in different states.

The CRZ 2011 only gives broad directions on the purpose and composition of DLCCs. It would have been important for the MoEFCC to notify an amendment clarifying the role of the DLCCs and reaffirm their importance in coastal governance. Doing this would show the government’s intent to realise decentralisation and devolution of powers, which goes beyond the ‘centre vs state’ tussle on decision-making.

With no such step taken so far since the promulgation of the notification, SCZMAs have worked with DLCCs in a variety of ways. For instance, according to the minutes of meetings held in 2013-14, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have involved DLCCs in the task of conducting public hearings on Coastal Zone Management Plans (CZMPs) and seek feedback from them on project proposals that require approvals.

Gujarat, Maharashtra, West Bengal and Karnataka have empowered DLCCs to take cognizance of violations suo moto and on complaints received by them. This is evident from the constitution orders issued by each of the SCZMAs between March 2011 and October 2013.

As per the State Government orders constituting DLCCs, the committees have been authorised to take appropriate steps to act on the violations. Gujarat, Maharashtra and West Bengal empower their respective DLCCs to remove illegal structures and encroachments and they can take help of the district police authorities for the same.

In Karnataka, the DLCC has to take action as per the directions given to them by the KCZMA. In Tamil Nadu, the district level institutions or DCZMAs have been made responsible largely for monitoring and enforcement of the CRZ notification. Using Section 4 of the CRZ Notification 1991, they have been empowered to take action on violations. However, how these powers are being used by the DLCCs could not be tracked from the meeting minutes obtained from SCZMAs.

Membership

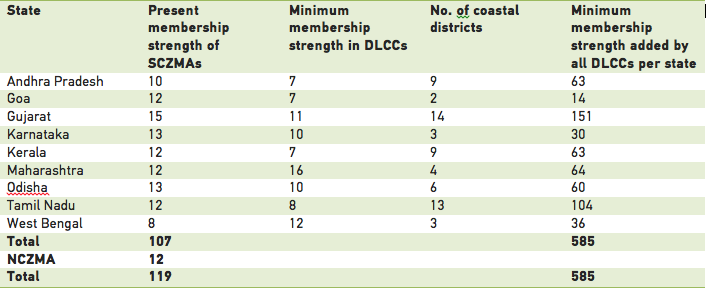

In each of the states where DLCCs have begun functioning, the number of members varies from 7 to 20 members. The minimum is in Kerala, where there are 7 members and the maximum is seen in Ganjam District of Odisha with 20 DLCC members.

The representation of traditional fisherfolk on the DLCC is a minimum of three persons as suggested by the CRZ notification, 2011. In all cases except the following, the figure remains three. In Karnataka’s districts, it ranges from three to five people, in Jagatsinghpur district of Odisha it is five and in the districts of Tamil Nadu, the representation of traditional fisherfolk is nil.

The information related to constitution of DLCCs in various districts received through RTI responses indicates that the Pollution Control Board (PCB) is a member of all constituted bodies. The Superintendent of Police and coastal experts have also been made members in DLCCs of Maharashtra and West Bengal.

Though the composition of DLCCs does provide for membership of various government departments managing the coast, their representation is much greater than the non-departmental members. This could cause conflict especially as government departments could violate clauses of the notification or abet it.

To cite an example, Gujarat made it mandatory for the Department of Ports to be a member in the DLCCs of the state. It is important to contextualize this move in light of the fact that the state of Gujarat has 40 major and minor ports, second only after Maharashtra (Indian Ports Association, undated). Their membership in the DLCC can have an important influence on the decision making, especially in instances when action needs to be taken on violations by port projects and on carrying out tasks of conservation.

Similarly, irrigation or canal divisions of the state have been brought into the membership of DLCCs in Odisha.

Making DLCCs work

It has been over four years since the new notification was issued and commitments were made to improve coastal governance and the lives of people that depend on coastal space and resources. DLCCs are key to the realisation of such commitments.

However, as the analysis above shows, there has been almost no attention paid to this layer of coastal governance. They are yet to be set up in two states: Goa and Andhra Pradesh. In other districts where they have been set up, they are yet to find their voice.

Orders, directions and circulars issued by the MoEFCC to the SCZMAs have never mentioned DLCCs, leaving one to believe that they don’t exist. While the SCZMAs report regularly on their responsibilities and decision making, there is little by way of documenting the day-to-day functioning of the DLCCs.

Except in Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, DLCC meetings and decisions may not even be documented and therefore invisible to themselves. They are quite naturally unavailable to researchers and policy makers also.

DLCCs form the fulcrum of the institutional structure for the implementation of the notification, a crucial bridge between coastal communities and the law. They need to be carefully shaped and nurtured as an institution, built up with capacity, resources and powers, studied and advised for good practices and monitored for the best possible outcomes.

REFERENCES

- MoEF team, Ministers to discuss CRZ norms today, The Hindu, 22 August 2014

- Recognise rights of fishing community: NFF, Deccan Herald, 24th May 2008

- Indian Ports Association: State Wise Number of Ports, accessed on 4 March 2015

- CZMAs and Coastal Environments: Two decades of regulating land use change on India’s coastline. CPR-Namati Environment Justice Program, India (in print).

- Coastal Zone Management: Better or Bitter Fare? Economic and Political Weekly, Vol – XLII No. 38, September 22, 2007, pp 3838-3840

- NFF (National Fishworker’s Forum) Report 2011, as on 4 March, 2015

- Coastal regulation zone norms: Central team to submit report in October, The Times of India, 24 August 2014.

This was first published in indiatogether.org, with the support of Oorvani Foundation – community-funded media for the new India.