News & Blogs | Stories

Justice & Identity in Kibera

Kibera, reputedly Africa’s largest informal settlement, is not an easy place to find your way around. Street names are, as you might expect, non-existent and landmarks are essential. If you wish to visit the Nubian Rights Forum (NRF) you first make your way to the Kibera Law Courts building. From the courts, NRF will guide you by telephone, past a relatively new ultra-high street light designed to deter crime, to the Makina Jamia Mosque.

However, so small is the NRF office that I sit across the street in my taxi without noticing it. A paralegal comes to escort an embarrassed me, the final five meters to the office. To get to the door from the road, you leap across a drainage ditch.

Kibera was once all Nubian. Originally from the Sudan, the Nubians were recruited into the imperial forces of the British late in the 19th century. As a reward for service in the King’s African Rifles they and their families were awarded an area of ‘kibra’ – wooded jungle – outside their barracks on the southwestern side of Nairobi.

Any jungle has long since disappeared, and Kibera is no longer all-Nubian. Waves of rural immigrants from across Kenya have made it a multi-ethnic home to an estimated 170,000-300,000 people. Most people live on less than $1 a day. Disease, crime and overcrowding rub shoulders with resilience and bustle. The main streets are crowded with micro-entrepreneurs selling charcoal, plastic kitchenware, and SIM cards.

Life in Kibera is hard, but it is harder still if you are a Nubian Kenya. After independence, the Kenyan state refused to easily recognize Nubians as citizens. Despite the community’s presence in Kenya since well before 1963, one of the requirements for citizenship, Nubians continue to suffer from insecure citizenship rights. They are subject to discriminatory “vetting” procedures that don’t apply to other Kenyans and face long delays in applying for documents like birth certificates, ID cards, and passports.

“Without citizenship, you are absolutely useless in Kenya,” says Shafi Ali Hussein, chairman of NRF. “It amounts to economic, social and political discrimination. Young people are arrested or harassed by the police without ID, they can’t get a job, their future is not good and life is a mess. They can’t get a passport to go and work in the Gulf. They cannot open a bank account or use M’Pesa”. M’Pesa is the Kenyan mobile phone-based banking service.

Since 2013 Namati, the Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI) and the Nubian Rights Forum have been using trained community-based paralegals to assist members of the community in securing ID cards, passports, and other essential identity documents. The paralegals help in the filing of forms, prepping clients before vetting and tracking documents among other activities in the application process.

Citizens trained as paralegals to empower their own community are at the heart of Namati’s approach, whether it is citizenship rights, helping villagers protect their communal land or ensuring that health clinics treat patients without asking for bribes.

Left to right: NRF staff Makkah Yusuf, Shafi Ali Hussein, Zahra Khalid Osman, Mustafa Mahmoud, Zena Abdulrahman Musa and Hassan Abdul Kassim

Mahmoud Abdullah Hussein

Mahmoud, who is 29, knows the difficulties living without ID causes Nubian Kenyans. Sitting outside the NRF offices, he tells me he is an artist and sign writer by trade, who grew up down one of Kibera’s alleyways in a one-room home with no electricity or running water. “I work painting signs in big offices. But you need to show an ID card now to get into many office buildings,” says Mahmoud. “Many times I was turned away and lost my work because I had no ID.”

Mahmoud was also forced to pay a fee to others to use M’Pesa to receive payments or transfer money for him when he was able to get some work. “I was trying for more than five years to get ID. But the Government office kept telling me to go back and get more tickets and more documents. They asked for the birth certificates and ID cards for my parents – my father is dead, yet they wanted his ID card. My mother had lost her ID card. I walked many times to the office and I lost hope – I thought they were playing a game with me.”

Mahmoud heard about NRF through one of their regular door-to-door outreach campaigns and he came to the office to meet Hassan Abdul Kassim, one of NRF’s paralegals.

“When I met him I asked about any documents at that he had and discovered that he had an ID card from one of his grandparents,” says Hassan, an imposing and charismatic young man who knows Kibera like the back of his hand. “I also asked him about his school and we went there and obtained a copy of his leaving certificate. The mother who raised him is his foster mother, so we could only use her as a back-up. But the with the right forms filled and the grandparents ID and leaving certificate it was simple enough to get him ID.”

“It took two months”, says Mahmoud still disbelieving. “When I tried for five years! Now I am in the process of getting a birth certificate so I can get a passport. I would like to work in Saudi Arabia. I will make big changes in my life with these things.” Hassan tells me as Mahmoud walks away that the young sign writer has himself now helped ten other people to get ID cards or brought them to NRF.

Saddam Tari

The next young man to tell me his story, Saddam Tari, 24, has lived all his life in Kibera and has the ambition to go to college to study mechanical engineering so he can work with cars. His story illustrates the extra hurdles Nubians face in getting identity documents because his dispute is with the vetting committee of Nubian elders.

This committee – an extra-legal institution that only operates in some Kenyan communities – is supposed to verify that applicants are who they say they are. One member of the committee is Saddam Tari’s landlord. “I was born in his house and he has known me since I was a baby,” says Saddam. “But he turned me away from the elders committee because we are in a dispute about rent.” Saddam shares two rooms with the eight people in his family. Their erratic electricity supply is tapped from their landlord’s meter. Water is collected from nearby. The going rent in Kibera is 5,000 Kenyan Shillings (US$50) a month for two rooms. “We are being chased out by the landlord because he wants to put it up.”

“He has his birth certificate, his leaving certificate from school, the death certificate of his father and his mother’s ID card,” says Hassan. “There is no question of his citizenship. So we are filing directly with the Government register office. I am sure we can make progress.”

“I am going to start calling colleges to look for a place,” says Saddam. “I am already telling many people that it is much easier with NRF.”

Khadija Hamsa

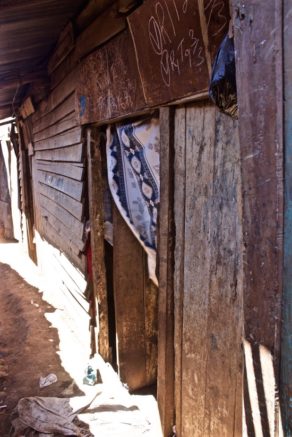

To hear Khadija Hamsa’s story we have to leave the main road, by the NRF offices, and venture down some of Kibera’s alleys into the heart of the settlement. Hassan’s bulky presence is reassuring, it’s his neighborhood and everyone says hello, as we step gingerly over trickling streams of water between mud, timber, and concrete block homes with corrugated iron roofs.

Khadija’s home is a wooden structure with a dirt floor. The only light comes from the doorway and the gaps in the eaves. Old curtains and cloths are draped on the walls. The roof leaks when it rains. A small kitten threads its way along an old sofa where two children sit. Khadija, who is 24, has five children and was born and raised in Kibera. She has no ID card, which means she can’t join a Government-funded work scheme clearing the streets for a small wage.

She has been trying on-and-off for eight years to get an ID card. “When I went on my own to the registration office the officials were rude to me because I am a Muslim and a Nubian. They asked me lots of questions and they asked for the birth and death certificates of my parents and grandparents – yet all my family is dead. Every time I bring one document they send me away to get more.”

As well as the work scheme, an ID card would enable Khadija to secure birth certificates for her children – their school has been asking to see their birth certificates and she is worried. NRF’s Hassan managed to get a copy of her school leaving certificate, which can be used to prove her identity and age. He is also preparing her for the vetting process – Hassan coaches her on what questions will be asked and how to answer them. “The officials are very tricky,” says Khadija. Hassan is confident she will have her ID card within six months.

Ayeesha Nasser

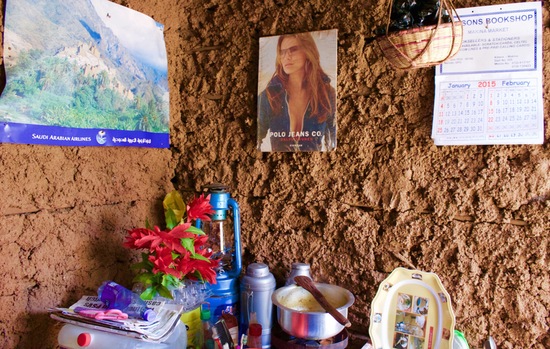

In a one-room house with posters on the mud walls, Ayeesha Nasser, 38, explains that she started her ID card application ten years ago but things have become both confused and more urgent at the same time. First there has been some kind of mix-up involving her sisters’ ID application that has stalled her own attempts to get an ID. She has also been told at times that she cannot be Kenyan because she doesn’t have a smallpox vaccination scar.

Ayeesha’s lack of ID means that she too has been unable to get on any Government work schemes. This, she says, means she could not support her children. One of her daughters lives outside Nairobi with her father and the other is in foster care. Being unable to support her children is clearly painful for Ayeesha, but it is not the worst of her problems. Ayeesha is HIV positive. When she found out she went to the hospital to ask for anti-retroviral (ARV) drugs to manage her condition. The hospital gave her three months of medicine but told her she really needed to have an ID card. They say she needs the ID card if she wants more ARV medicine at the end of the three months.

“We have applied for copy of the death certificate of her father,” explains Hassan. “And we should be able to get a leaving certificate from her madrassa. With these, we can get her an ID card. The problem is that the vetting committee says that it is full up for the next three months – it only meets once a month – and we need to get her and ID card as quickly as possible so she can continue her treatment. We will go and plead with them to add her to their list for the next vetting meeting.”

As we leave Ayeesha’s home Hassan explains that searching for a vaccination scar as proof of nationality is simple discrimination. “This is a common issue because sometimes the scar just doesn’t appear,” says Hassan. “For other Kenyans, non-Nubians, it isn’t a problem if the vaccination mark is not there.”

Hassan says he knows young men who have joined the gangs in Kibera because they had no other way of making an income without identity documents. He is now helping several who wish to turn away from a life of crime. “They are often scared to go near officials because of their previous activities,” says Hassan. “I have helped about 14 youth who want to make their lives legitimate. Everyone is learning – if they want to change their life they come to the Nubian Rights Forum.”

Photography and words by Paul McCann, with thanks to the Nubian Rights Forum.