Stories

The Loss and Delay of HIV Patients’ Lab Results

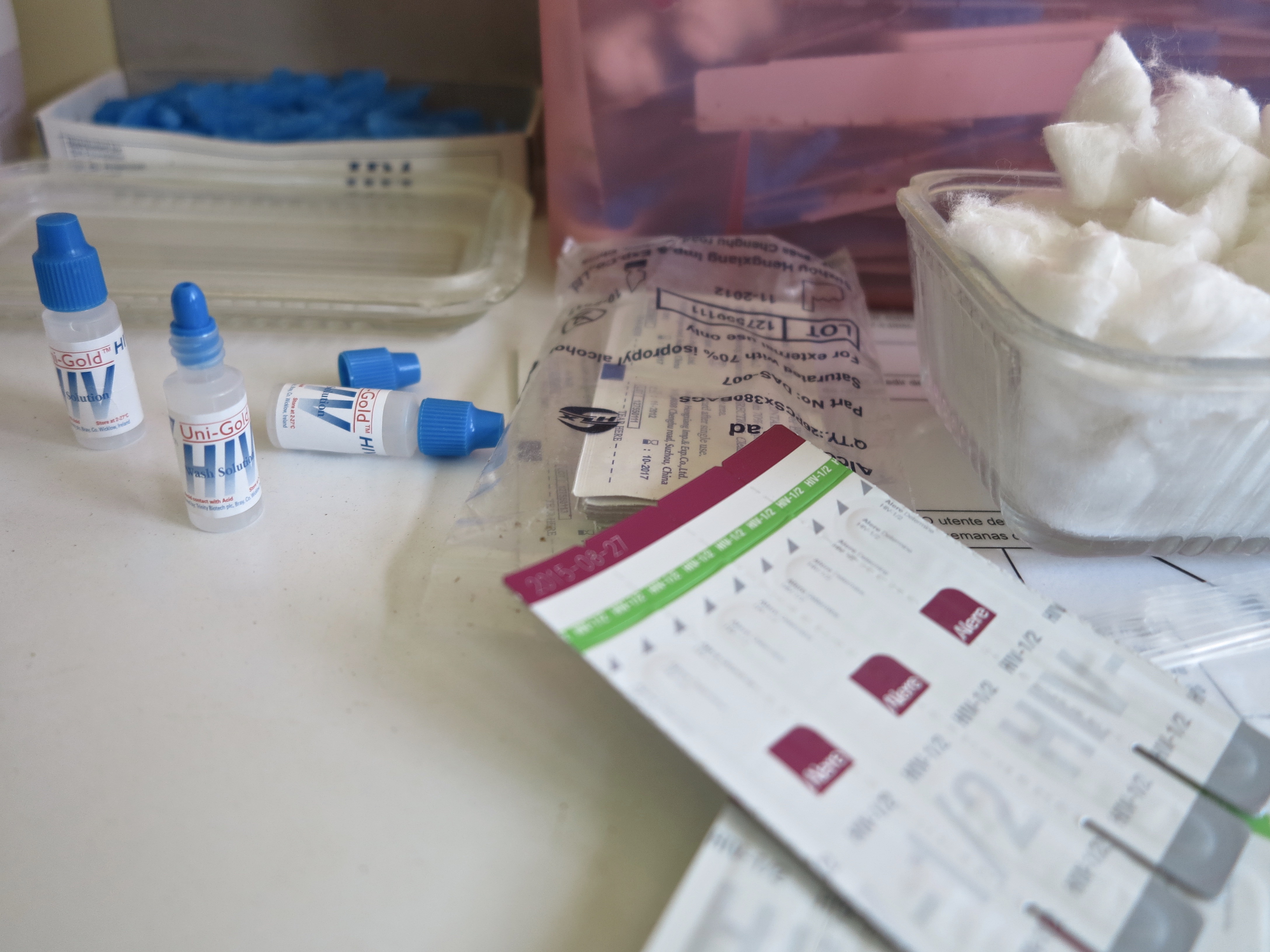

At a bustling health center on the outskirts of Maputo, Mozambique, nearly 8,000 patients living with HIV receive care and treatment. Despite the high volume, the health facility did not have a CD4 machine on-site for measuring the level of immuno-suppression in HIV patients. Blood samples had to be transported to a nearby hospital for analysis. Test results were frequently misplaced and delayed, sometimes for months. One of these patients—Jorge—had to return to the health center three times in October of 2015 to repeat his blood draw. Each time, he arrived by 6:30 am and, weak as he was, waited in line for more than four hours.

Both patients and a number of the center’s medical staff were frustrated by the situation. “I felt as though I was doing a real disservice to my patients—that I was unable to provide quality care in the absence of a CD4 history,” said one technician. “It was impossible to get results back, even for those who were gravely ill.”

One morning in October 2015, a group of six patients living with HIV approached Namati’s health advocate, Abudo, in the waiting area outside the HIV clinic. All of their CD4 results were missing. They asked for Abudo’s help in tracking them down.

The following week, Abudo, together with two of the patients, met with the head of the health center. They voiced their concern that the transport of blood samples and results was becoming increasingly disorganized. The head of the health center agreed and sympathized. She showed them a copy of a request she had submitted to district health management nearly two months earlier asking for a CD4 machine to be installed permanently at the facility. She had not received a response.

Abudo brought the case to Namati’s Right to Health program officer, Ofélia. They discussed the situation and decided that the appropriate next step was to request a meeting with the district director of health.

At the meeting, they spoke about the impact the delayed test results were having on patients’ lives, including money spent, time wasted, and increased illness. The district director agreed that given the high patient volume at the facility, a CD4 machine was justified, but in light of many competing priorities, she could not say when it would be procured.

Abudo and Ofélia were not to be deterred. As an interim solution, Abudo collaborated with the head of the health center to improve management of blood samples and results by introducing a logbook and limiting responsibility for transport and documentation to one driver who was trained and supported to take on this task. Patients and providers at the health center soon noticed marked improvements. Meanwhile, Ofélia continued to advocate at the district level for a CD4 machine, and in March 2016 a machine was delivered to the health center.

Jorge – the patient who had to return three times to have his blood drawn – was one of the 8,000 who benefitted from the arrival of the machine. “In the past, it was very difficult for me,” he recalled. “I live more than 20 kilometers from here. I was very weak, and it was not easy for me to get here every day to check on my results. I wanted to abandon treatment. Today, things are different. The care I get is much better. I know that when I come here I will have my results immediately.”