Post

‘Rule of law and post-2015: a menu approach’

Editor’s note: This piece first appeared on the World Bank’s Governance for Development blog and has been cross-posted with permission from the author.

By Nicholas Menzies

On Friday last week I attended the final session of the United Nations Open Working Group – the body tasked with putting together global development priorities to replace the Millennium Development Goals. The session covered rule of law, along with peace and governance.

With a few exceptions, most member states were supportive of the inclusion of rule of law in the post-2015 development agenda. This aligns with global public opinion reflected in the UN’s World We Want Survey – where issues such as honest and responsive government and protection from crime and violence rated above such development staples as roads and household energy supply. A side event to the Open Working Group on Friday highlighted all the ways in which rule of law is measurable.

Despite the general support, quite a few Open Working Group members raised the issue of how to include rule of law whilst also “respecting national sovereignty” and “promoting national ownership,” as well as taking into account that justice systems look different in different places.

Over the past 12 months, I’ve been involved in a range of technical meetings about the inclusion of justice and rule of law in the post-2015 framework. These get-togethers have grappled with the same general tension raised at the political level in New York – how to balance the global importance of rule of law with the local specificities of justice problems and systems.

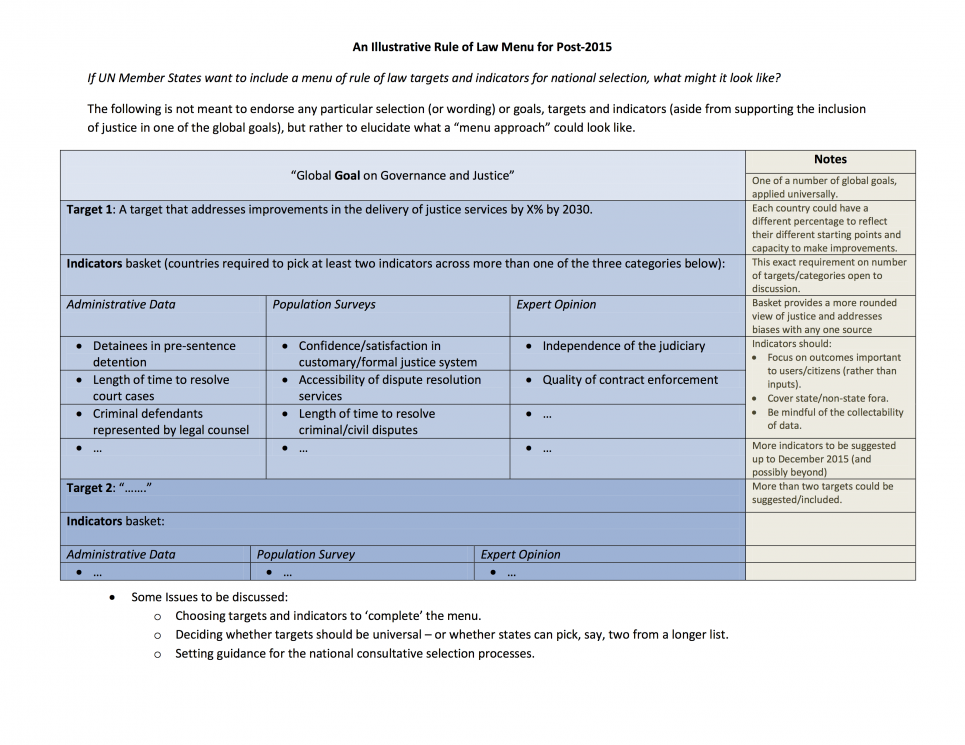

One way member states could consider addressing this tension is to adopt a global justice menu of targets and indicators underneath a universal goal on governance and justice. Each country could choose from the menu in accordance with their own conditions. Here’s what such a menu could look like:

Whilst there are a number of ways the menu could be set up, in one example, countries could be required to select at least two targets from a list of, say, five – maybe one country wants to focus on justice services and property rights; the other on legal identity and citizen security. Countries could also be allowed to choose the level of ambition in each target to match their starting conditions. It might be more reasonable to shoot for a 25% improvement in the efficiency of justice services in one country and only a 10% in another. This is not to say that justice services aren’t important in the latter, but the conditions might mean only a small – but still meaningful – improvement is possible.

Whilst there are a number of ways the menu could be set up, in one example, countries could be required to select at least two targets from a list of, say, five – maybe one country wants to focus on justice services and property rights; the other on legal identity and citizen security. Countries could also be allowed to choose the level of ambition in each target to match their starting conditions. It might be more reasonable to shoot for a 25% improvement in the efficiency of justice services in one country and only a 10% in another. This is not to say that justice services aren’t important in the latter, but the conditions might mean only a small – but still meaningful – improvement is possible.

Under each target a basket of indicators could be suggested and countries could be required to select across a range of data sources – administrative data, expert opinion and population and user surveys – approximating the breadth of the concept of justice. They could even suggest their own.

One benefit of this approach is that it would necessitate dialogue between citizens, users of the justice systems and their governments: about the most pressing justice problems; how far they want to get during the post-2015 period; and how they’ll know they’ve got there. This may serve to build national accountability relationships – not just reporting ones between member states and New York. Establishing principles to guide the process of building and sustaining meaningful dialogue would be critical and here the international community could play an important role in collaboration with national and local actors. These dialogues would also allow focus on measures for which data is collectable – perhaps reducing the number of empty cells that have dominated MDG reports since 2000.

There are some risks. Countries could low-ball by picking underwhelming targets or ‘easy’ indicators that can be met with minimal effort. There are also some questions about how a variable justice menu might cohere if the rest of the post-2015 framework contains universal targets and/or indicators – though it could well be that other sectors also decide to adopt their own “menus”.

The Open Working Group is now negotiating the world’s development priorities up until 2030. Member states and the world’s population agree that rule of law is important to development and needs to be included. Adopting a global menu of justice indicators and targets is a technically feasible way of balancing global priorities with local needs.

Nicholas Menzies is a Justice Reform Specialist in the Legal Vice Presidency of the World Bank. He works on institutional reform of the formal justice sector and on mainstreaming justice into development programming with the Justice for the Poor program, with particular interests in impact evaluation, indicators and gender. Prior to the World Bank, he worked at the intersection of plural legal systems as a land and natural resources lawyer for indigenous communities in Australia, on legal empowerment and access to justice issues in Cambodia, and in providing policy advice to the Papua New Guinean cabinet. Mr. Menzies has an LL.B. and a B.A. from the University of Sydney and a Master of Public Policy degree from the Hertie School of Governance, Berlin.

Nicholas Menzies is a Justice Reform Specialist in the Legal Vice Presidency of the World Bank. He works on institutional reform of the formal justice sector and on mainstreaming justice into development programming with the Justice for the Poor program, with particular interests in impact evaluation, indicators and gender. Prior to the World Bank, he worked at the intersection of plural legal systems as a land and natural resources lawyer for indigenous communities in Australia, on legal empowerment and access to justice issues in Cambodia, and in providing policy advice to the Papua New Guinean cabinet. Mr. Menzies has an LL.B. and a B.A. from the University of Sydney and a Master of Public Policy degree from the Hertie School of Governance, Berlin.