Stories

“The Cleaner was Giving Vaccinations”

As you drive north out of Maputo, Mozambique’s capital city, you pass a stretch of beach where, at low tide, people are digging for clams – both for themselves and for the city’s seaside restaurants. A little further north and the road turns to sand that has been leveled – so it can be tarmacked by the Chinese company that is building a new road.

As you progress, past hand-painted buildings advertising mobile phones or beer, the houses become less dense, small fields appear for livestock and tall corn stalks grow beside the bumpy side roads.

I have come to the edge of Maputo to meet a village health committee and Namati Moçambique’s local health advocate – the lively, smiling Leopoldina Nhamposse, known locally to everyone as Dina.

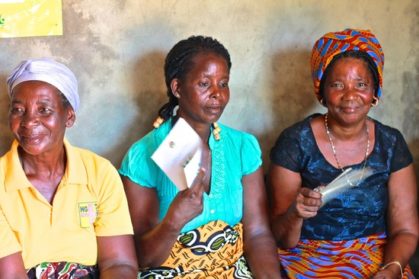

The health committee members are waiting in a stifling community building behind the village health center. They are eight dignified and handsome women, mostly in their forties and fifties, and two serious gentlemen. The women wear bright campulanas, the traditional long, patterned skirts of Mozambique.

Antonio M, the chairman of the health committee starts to tell me about their history and purpose. How they were created eight years ago and saw one of their tasks as to ensure people in the community followed their health regimens. He tells me how since the arrival of Dina in 2014, the focus has shifted to the quality of services the community receives from the clinic.

“The health advocate has facilitated our work so much,” say Antonio. “What has really improved is the chronic lateness of the health staff. Before we really struggled to defend the community’s rights to be seen by health providers. We tried to have meetings with the health director or we wrote letters that were never responded to. When Namati arrived it gave legitimacy to our work and the director of the clinic became responsive.”

Celeste M, a member of the committee in a vibrant orange and blue headscarf fans herself as she talks: “People didn’t want to come here before because they were badly treated. In the past the person giving out numbers for the appointments was always late or would go away for lunch. There were also staff who took bribes to let people jump the line. If someone is gravely ill, they should be seen first, that is the policy, and now we’ve made it happen.”

“Now with Dina’s arrival, bribery has been completely eliminated,” adds Antonio. “She gave talks, day after day, that bribes are undermining people’s health and she sensitized the staff and the community that bribes are illegal. She also came early each morning and noted the arrival time of the staff. She has to leave her house at 4.30am to get to the clinic by 6.30am, so she knows who comes on time. The staff talk among themselves about her – they say ‘has Dina arrived, did you see her?’ They now know they have to come on time.

Staff absences are a major issue for health systems in economically under-developed countries because the salaries of medical technicians are not high and some are forced to supplement their income with other jobs. There are also very few qualified nurses in Mozambique, giving them a level of impunity about their attendance – until Dina arrived.Dina tells me about one particularly bad case of absenteeism:

“In the antenatal section a nurse was chronically late and would see only five patients a day, then say ‘I’ve seen the limit for today’. The women told me about it when I gave my morning talks about health rights to the people waiting at the clinic. I went to speak to the director who agreed to monitor the antenatal nurse for 30 days. She told her she would lose her job. Now she sees 20 patients every day instead of just five.”

In another case, at a satellite health post linked to the clinic, the village health committee was told that a cleaner was giving vaccination injections to babies. The committee investigated and discovered the cleaner was trying to help – local mothers told them the nurse was always late or absent. The committee spoke with the head nurse and the absentee nurse from the health post, and managed to improve her attendance.

I ask Dina if monitoring the staff hasn’t made her unpopular, but she says she spoke with all the staff at the clinic individually when she arrived and explained they had the same objectives – to help the patients. “Now sometimes they bring me cases,” she says. Every month now Dina reads her monthly report on the clinic to a meeting of all the staff.

Dina gives an example of how by working together, a health advocate and the staff can improve things for patients: “There were no sheets or blankets in the delivery rooms and mothers had to give birth on plastic mattresses. The head nurse said they had to send their sheets and blankets to a local hospital to be washed, where over time they were stolen and now they had nothing. I put pressure on the head nurse and she put pressure on the regional health authority and a month later they received 12 set of sheets and blankets and mosquito nets. Then we secured some insect screens for the windows, when I first came there was nothing. Now, whenever I see those screens it makes me feel happy.”

At this point our conversation is interrupted by a woman who wants to talk to Dina – to tell her, her appointment had just been canceled for the third time. Clearly, improvements can still be made.

We tour the clinic which has a small crowd surrounding it waiting for their appointments with nurses, technicians and the small, over-crowded pharmacy. We are shown, by the staff, a stockroom piled to the ceiling with anti-retroviral medicines. Other cartons of valuable medicines are stacked in the hallways. Needless to say, stock and quality control must be very difficult in such circumstances – medicines could easily be pilfered and almost none seem to be refrigerated.

This clinic, just outside Maputo, has a population to serve of around 40,000 people – and that is only the official estimate of a growing district. To provide them with healthcare, the director of the clinic has just 20 staff – many of whom transfer in and out frequently. Dina and the village health committee are a crucial tool, both to help a severely stretched public service improve its provision to the local people and to help those people secure their rights to health.

“The health advocate really helped us get more respect from the health providers,” says Celeste from the health committee. “And now we are seeing a change in the treatment people receive.”