AGHANASHINI, KARNATAKA

The Aghanashini River is one of the last entirely free-flowing rivers in the World. Near the coast, the estuary’s beautiful and ecologically rich environment supports the livelihoods of local communities who fish, harvest clams and oysters, and depend on its precious ecosystem in myriad ways. This coast supports a rich variety of wildlife and has 16 species of mangroves, a uniquely highest diversity for mangrove forests.

The estuary is a zero investment industry. Every year it produces 22,000 tonnes of bivalves valued at Rs 58 million. 40% of the collectors and sellers are women.

Coastal farming is also an integral part of this landscape. Farmers grow a special and flavorful salt resistant variety of rice, called Kagga.

Hema Gouda sits with her mother Gange Gouda during the harvesting of the peanut crop. Aghanashini Village, Karnataka State, India.

“I used to work as a clam collector, so I have a strong belief in the work and protecting it.” – Maruti Gouda

Paralegals trained by Namati and the Centre for Policy Research (CPR) work with the Aghanashini community to establish a union of clam harvesters. Previously, clam harvesters were not recognized by the government as fishermen and therefore unable to join any union. This resulted in clam harvesters not being eligible for government compensation schemes in the event of death or injury at work.

“As a community we’ve been trying for more than 25 years to get government recognition of our rights to be recognized as fishermen and to form a union to protect our rights. Working with Namati and CPR, it’s taken just eight months of work to achieve the same thing.”

Maruti Gouda, a paralegal working for Namati, convenes a meeting of the newly formed members committee of the Aghanashini clam harvester’s union in Aghanashini Village, Karnataka State, India.

There is a long history of large scale development proposals on the Aghanashini River. Most other rivers in the state, and much of its coastline, have not escaped environmental damage cause by poorly managed industrial development. Presently a large port, capable of handling seafaring container ships is proposed for the estuary. If it goes ahead the required dredging and subsequent river traffic will disturb the river’s delicate ecosystem and affect the livelihoods of the clam harvesters and many others who depend on it. Namati-CPR paralegals work with communities living along the river’s estuary to understand the full range implications of the proposed development.

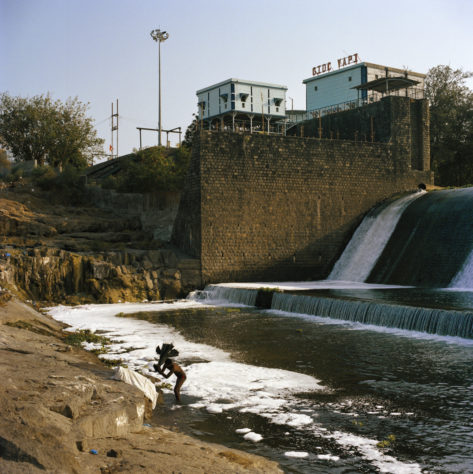

VAPI, GUJARAT

Vapi, an industrial city on the south coast of Gujarat State, is ranked by the Indian government as one of the top four sites in the country with critically high pollution levels. There are as many as 700 small to medium scale chemical production plants in the city. Vapi’s environment is noxious. It is known as the ‘Armpit of India.’

Much of the chemical waste finds its way into two nearby rivers, the Kolak and the Damanganga. A Common Effluent Treatment Plant is operated by the Vapi Industrial Association and monitored by the Gujarat Pollution Control Board. Due to the plant’s low capacity and failure to properly treat the effluent before release, the water downstream runs black and supports no life.

The Billkhadi creek flows into the Kolak River carrying industrial chemical pollution from Vapi’s industrial development zone. Vapi is a growing city and residential developments can be seen sprouting up across the city. They have names like ‘New Palace Gardens‘ and ‘Sun Residency‘.

A residential development on the banks of the Billkhadi brook, which flows into the Kolak River and carries industrial chemical pollution from Vapi’s industrial development zone released into the river without proper treatment.

Before the rise of chemical industries in Vapi most people in Kolak depended on fishing in the river’s estuary waters for their livelihoods. Catches are severely reduced and people worry about the safety of eating fish caught in the estuary’s polluted waters. Communities dependent on fishing in the estuaries have been forced to relocate or seek other means of securing their livelihoods.

Namati works with communities affected by chronic pollution to find remedies to their long standing impacts.

Manisha Goswami, a mother of two children and a Namati-CPR paralegal, works on cases with communities affected by pollution and helps authorities enforce environmental regulations such as the Pollution Acts and the Coastal Regulation Zone to tackle industrial pollution.

“My daughter’s asthma inspired me to take action initially, as a community activist. Now, working with Namati, we use an evidence based approach and use the Right to Information Act to access government data, such as compliance and monitoring reports.”

She seeks the enforcement of regulations by government authorities, especially the proper treatment of Vapi’s chemical industry’s waste water before its release into the Daman and Kolak rivers.

Manisha Gosuami, a mother of two children and a Namati paralegal, stands amidst waste from the chemical industry in Vapi’s industrial development zone.

“In the Kolak river case, where we are seeking compensation for two fishermen’s communities for damages caused by environmental destruction of the river’s estuary caused by untreated effluent from the chemical industries in Vapi, we have 10,000 fishermen who are signatories to the case.”

Villagers who are signatories to a case for compensation brought by Namati paralegals to the Gujurat state authorities.

The Daman River passes by a playground and the harbour at the river’s mouth. The water’s colour is a result of pollution originating in Vapi’s chemical industries.

Two boys fish their cricket ball out of the Daman river where it passes by a playground and the harbour at the river’s mouth.

Photographs by Aubrey Wade for Namati – www.aubreywade.com

Locations: Aghanashini River, Karnataka State; and Vapi, Gujurat – India