A woman collects water from a local water pump in a village in Gujarat state, India

Our Journey in 2019 & 2020

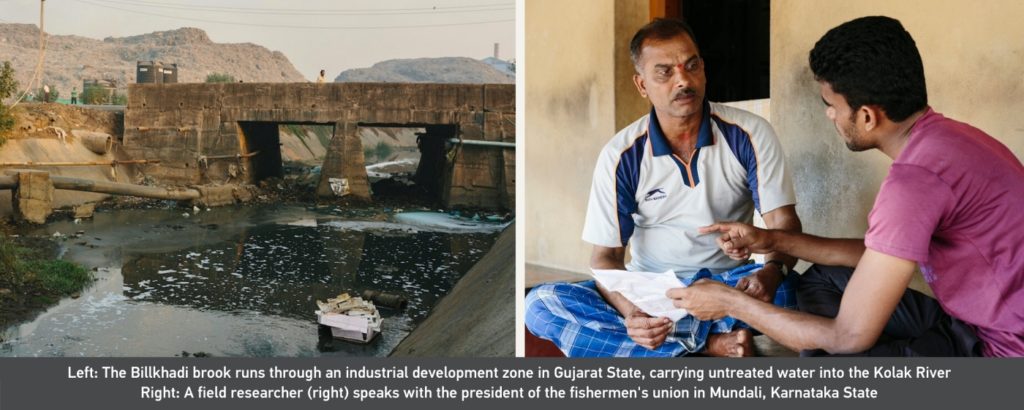

On paper, mining, industrial development, and other private and public projects in India must adhere to strong regulations that serve to mitigate their environmental impacts. In practice, there is a very poor record of compliance and enforcement. From poisonous chemicals dumped into the waters of fishing communities, to hazardous emissions polluting the air, unlawful practices are endangering the health and livelihoods of local communities and damaging the environment.

One key reason for this systemic failure is that the people facing environmental harm have almost no role in either the creation or implementation of the rules and systems that are meant to protect them.

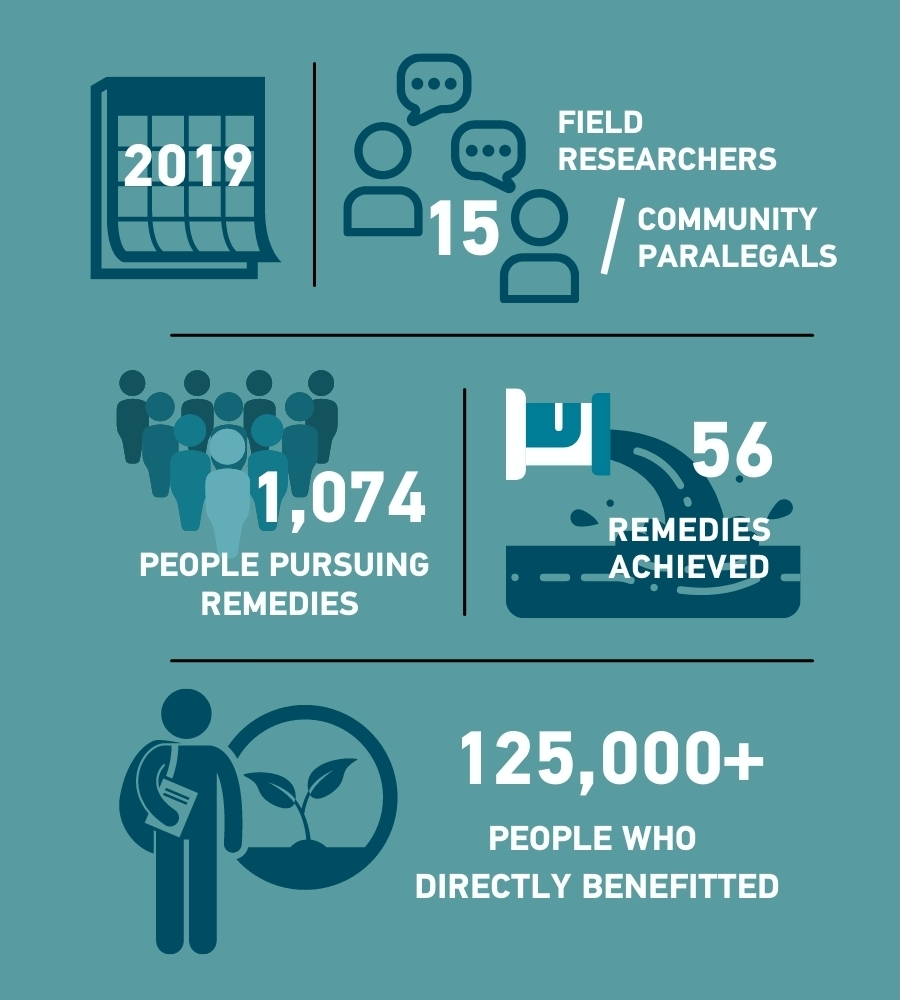

Our Grassroots Impact at a Glance

In 2019 and 2020, paralegals supported communities to address instances of environmental non-compliance by companies and public projects. Together, they achieved remedies that directly improved the livelihoods and wellbeing of thousands of people.

Two bauxite refinery chimneys emit thick smoke, leaving a layer of toxic dust behind

Forty Years of Toxic Dust: How a Rural Community in India Displaced a Refinery

You could see it from the Dwarka-Khambaliya National Highway. Mountains of crushed aluminum-rich ore, uncovered. Chimneys spewing thick, dirty-looking smoke.

Everything within half a kilometer of the bauxite refinery was covered with a layer of toxic reddish dust — a school, government hospital, farmlands, and the village of Harshadpur included.

Biren Singh’s* house, a modest concrete structure, was located 100 meters from the refinery’s low perimeter walls. “We faced a lot of trouble because of the dust,” says the farmer and father of two. “It was difficult to breathe properly. [It] spoiled our crops; the dust would sit on the flowering crops and would stunt their growth. …We would not even hang our clothes to dry because within a few hours they’d be laden with dust.”

Writing to Grow the Movement

We aim to communicate the urgent need for land and environmental justice to policymakers and people across India. To that end, in 2019 and 2020 the Centre for Policy Research-Namati program published op-eds and had our work featured in numerous mainstream media outlets.

)

In the Press

Environmental Exemptions Now Allow for Piecemeal Expansions of Coal Mines

)

In the Press

The Draft EIA 2020 notification and everything that is wrong with it

)

In the Press

NH 66 expansion hit more lives, ecology than estimated: Study

)

In the Press

The New Coastal Law Sets an Unethical Precedent in Policy Making

)

)