Post

Mapping Community Lands Requires Accountable Land Governance

Many within the global development community have begun to advocate for rapid campaigns to map, document and protect community lands as the global land grab appropriates land from rural communities at an unprecedented pace. Community land documentation efforts (which document the perimeter of a community according to customary or indigenous boundaries) can be a low-cost, efficient way to protect communities’ customary land claims.

Broad-scale mapping efforts – and strong legal protections for community lands and natural resources – are urgently needed: common properties and community lands not currently under cultivation are often the first to be allocated to investors, claimed by national and local elites, and appropriated for state development projects. A global map detailing rural communities’ land claims has the potential to make clear to outsiders that seemingly “unused” forests, pastures and water bodies are actually the site of millions’ of peoples’ livelihoods and the source of all of their food, water, building materials, traditional medicines, and other materials necessary to their basic survival.

However, if community land mapping efforts are undertaken without accompanying community empowerment efforts that promote good governance of local lands and natural resources, they may create more harm than good, for two main reasons.

First, as James Scott stated so well in his book “Seeing Like a State:” what is mapped is made transparent and known; what is as yet unmapped remains obfuscated and “mystifying to outsiders.” Most critically, when land is mapped and titled, it is more easily sold and transacted on the market. Indigenous and customary communities may not want to be so easily identified on a map by outsiders. And government aid agencies may push for mapping not for protection, but with the motive of more quickly fostering a land market in regions rich with natural resources.

Second, while documentation of community land rights provides protection against land usurpation by outsiders, it does not protect against intra-community threats: leaders with a map and no downward accountability can sell or transact community land much more easily. There have been ample reports of chiefs redefining their customary stewardship of land as being actual “ownership” and then selling common lands for their own profit.1 Chimhowu and Woodhouse have noted that: “[T]hose with greatest influence over land under customary tenure (tribal chiefs and heads of patrilineages) will be best placed to gain from the commoditization of land through sales and rents.”2

To state it plainly: providing a poorly governed, disempowered community with documentation for its land rights without ensuring intra-community mechanisms to hold leaders accountable to good governance may, in some instances, make land dealings even more unjust and quicken the pace of land alienation.

Community mapping and documentation initiatives that do not support communities to establish systems for transparent, just, and equitable administration of those lands will likely invite mismanagement, corruption, and local elite capture. They may also further weaken women’s land rights by inadvertently entrenching discriminatory norms that exclude women from land governance and undermine their inclusion in community decision-making.

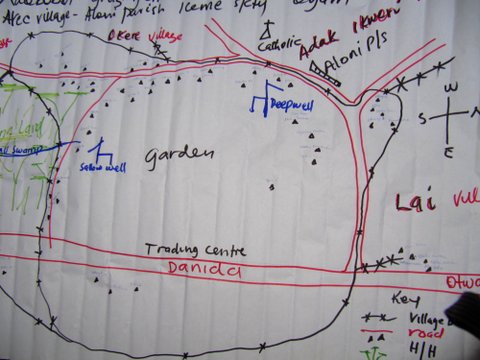

To address these concerns, community mapping and documentation should not be undertaken as a one-off GPS procedure. Rather, mapping must be accompanied by authentic governance changes that support communities to establish intra-community mechanisms to ensure good governance, intra-community equity, sustainable natural resource use, and authentic community approval for all transactions with outside investors. To do this, mapping procedures should be paired with the process of facilitating communities to draft and adopt community by-laws or “rules” for administration and management of lands and natural resources.

Examples of this approach can be found in Liberia, Uganda, and Mozambique, where Namati – in partnership with the Sustainable Development Institute, the Land and Equity Movement in Uganda, and Centro Terra Viva respectively – works to support communities to follow formal legal procedures to map, document and protect their lands. In the course of the process, field teams facilitate groups of men, women, youth, and elders to undertake an inclusive and holistic by-laws and natural resources management plan drafting process. This by-laws drafting process has six discrete parts:

- An uncensored, highly participatory “shouting out” or brainstorming of all existing community rules, norms and practices for land and natural resources management, which a community then captures in writing as the 1st draft of their by-laws;

- Community analysis of these rules in light of evolving local needs, followed by participatory discussions that lead to amendment, addition or deletion of rules, leading to a 2nd draft;

- Community-wide education about relevant national laws and human rights principles;

- Community analysis, discussion and debate of the draft by-laws in light of national laws and community interests, leading to a 3rd draft;

- A legal or technical “check” of the community’s 3rd draft to ensure compliance with national laws;

- A formal vote, in which a community adopts the by-laws by full community consensus or super-majority vote.

To ensure that by-laws drafting processes are fully participatory, facilitators should:

- Ensure that “the community” is defined as including all residents within the area to be documented, including women, minority groups, and others who may not have been born in the community;

- Undertake intensive and continuous community mobilization to ensure that members of all stakeholder groups actively participate in all debates and discussions;

- Convene special women-only meetings to identify issues that affect women’s rights and participation, and empower women to support one another to speak up to voice these issues during community meetings; and

- Plan community land documentation meetings to take place at convenient times and locations, after women and men have completed their house and farm work.

A highly participatory land documentation process has the potential to galvanize communities to improve intra-community governance, foster participatory rule-making, establish accountability mechanisms for local leaders, promote local conservation of natural resources, and support communities to create intra-community mechanisms to protect women’s land rights.

The by-laws drafting process often results in:

- The community as a whole making governance decisions usually made by leaders acting alone (see chart below);

- Women, youth, and other vulnerable groups questioning discriminatory customary norms and advocating for rules that strengthen both their land rights and their participation in land and natural resource governance;

- The institution of term limits, periodic elections for leaders, criteria for impeachment, and rules about what decisions leaders may make versus what decisions must be made by the community as a whole (such as whether to transact land with outside investors);

- Community members taking steps to modify local customary rules so that they no longer contravene national and human rights law; and

- Community members “remembering,” reviving or creating rules to ensure conservation and sustainable natural resources use.

This by-laws drafting process has provided community members with the opportunity to directly or indirectly challenge their leaders to better represent community interests, and to demand and establish transparency and accountability mechanisms.

For example, in one community, a few months after the by-laws were drafted, community members dismissed the customary manager of their grazing land when they discovered that he had secretly allowed some community members to encroach into the agreed common areas land and claim land for their own private use. Publicly decrying his actions as a breach of their by-laws, the community held a general meeting in which the manager was given notice. The community then evicted the encroachers, re-harmonized the boundaries, and re-erected the boundary markers that had been surreptitiously removed.