Post

Struggles in Suriname: Learning from Namati’s Community Land Rights Database

In January 2016, a headline grabbed me. After several months of volunteering with Namati’s Community Land Rights CaseBase, I came across news of an important legal victory for indigenous land rights in Suriname, a country I knew virtually nothing about. I had been collecting case law concerning community and indigenous land rights from across Latin America, many of which are high profile cases from countries well represented in global land rights debates, such as Brazil and Ecuador. Now, I found myself pulled into a small and underreported corner of the region by a story that was too compelling – and concerning – to ignore: the long and ongoing land rights struggles of the Kaliña, Lokono, and Saramaka peoples.

Suriname Stands Apart

Suriname is a densely forested country in northeastern South America with an economy that is heavily reliant on the export of gold, bauxite, alumina, and timber (1). The country’s indigenous and tribal peoples (ITPs) comprise approximately 25% of the national population but fall at the bottom of all social and economic indices, mainly residing in the inland forests that sustain their physical and cultural survival (2). Many of Suriname’s ITPs live subsistence lifestyles and retain a worldview at odds with western conceptions of the environment, wellbeing, and development—based on a spirituality that emphasizes the sanctity of ancestral territories that bind families across generations. ITPs in Suriname are increasingly under pressure to defend their territories and the mineral and timber wealth within them.

Suriname remains the only country in Latin America and the Caribbean that does not legally recognize ITPs as distinct minority groups, nor acknowledge notions of collective identities or rights (3). This situation is compounded by the constitutional status accorded to land and natural resources as state property by default unless formally given over to private ownership (4). The combined effect is to deny ITPs legal recognition of their ancestral territories, enabling the government to treat ITPs’ occupation of land as a privilege that can be withdrawn in the ‘general interest’ (a label that is broadly applied to all development projects) (5). This has enabled the government to legally lease 40% of Suriname’s total land area to private investors, with many concessions located within the traditional territories of ITPs (6).

The Case of the Kaliña and Lokono Peoples

It is within this context that the Kaliña and Lokono peoples brought their case before the Inter-American system in 2007. Suriname’s two largest indigenous groups have inhabited the Lower Marowijne River area for more than two thousand years, forging a livelihood upon agriculture, hunting, fishing, and gathering forest products (7). Yet encroachments upon their territory began after the State issued a bauxite mining concession in 1958, and was later aggravated by the creation of several nature reserves that restricted access to their traditional hunting and fishing grounds (8). The bauxite operations, in particular, had devastating consequences. Not only did they entail the stripping of large tracts of land and felling of trees considered sacred by the Kaliña and Lokono, but dynamite explosions, contamination of soils and waterways, and removal of forest cover, all caused wildlife to flee the area. Roads built to transport the mineral were then exploited by illegal loggers and poachers to exacerbate the harm already inflicted (9).

Faced with the environmental destruction around them, the communities turned to the authorities for help. However, the Surinamese judiciary rejected three cases in subsequent years citing a lack of legal grounds. As their pleas to the President of Suriname went unheeded, the Kaliña and Lokono were left with little choice but to seek assistance from outside the country, taking their case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) with support from the Forest Peoples Programme, a British NGO (10).

Upon reaching the conclusion that the government had violated the rights of the Kaliña and Lokono, the IACHR forwarded the case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) in 2013 for a binding interpretation (11). When the verdict finally arrived at the end of 2015, the Court ruled definitively for the Kaliña and Lokono peoples, finding violations of the right to legal personality, collective property, and judicial protection. Suriname was ordered to repair the damage it had caused by granting the communities formal recognition of their collective personality, demarcating and titling their traditional territory, rehabilitating the areas that had been degraded by mining, and guaranteeing these rights to all of Suriname’s ITPs (12). The decision was heralded as a major legal victory for indigenous peoples’ rights in the region and around the world. Despite the positive ruling, however, critical questions remain unanswered, chief among them being the extent to which this decision will influence a government that remains wedded to an export-led vision of development.

View the CaseBase entry about the Kaliña and Lokono case

Reflecting Upon the Plight of the Saramaka People

Some foreshadowing may be gleaned by assessing the outcome of an earlier case from Suriname. The case in question centered on incursions into the traditional territory of the Saramaka people, one of several afro-descendant tribal groups whose ancestors were brought to the country as slaves by European colonizers in the 17th century (13).

After escaping from their captors and establishing autonomous communities in Suriname’s remote interior, the Saramaka lived with little external interference following the abolition of slavery in 1863 (14). This held true for almost a century, yet it would be abruptly shattered when work commenced on the Afobaka hydroelectric dam in 1959. The dam flooded approximately 2000 square kilometers of pristine rainforest, destroying roughly half of the Saramaka’s ancestral territory (15). The government resettled up to six thousand people in ‘transmigration’ villages where, removed from their spiritual home, the Saramaka witnessed a steady disintegration of their society (16). Those who could migrated to the cities or joined other Saramaka villages that had been largely unaffected by the flooding. Eventually, however, even these communities were traumatized by State interventions.

From 1997 onwards, the State began issuing logging and mining concessions to investors eager to exploit the resources in Saramaka territory (17). Sylvia Adjako of the Matjau lö, or clan, was one of those particularly badly affected. Three of her farms were destroyed by a Chinese logging company operating with the support of the military, leaving her livelihood in ruins. Forced thereafter to rely on her relatives for food, she was unequivocal in her assessment of the dangers posed by the concessions:

“Our land and the forest is everything for us. It’s our life. What the Chinese did threatens our future, the future of all Saramaka … We cannot let this happen again or there will be no more Saramaka people, we will be like ghosts.” (18)

View the CaseBase entry about the Saramaka case

A Rejection of International Law

The Saramaka responded by launching several domestic and international legal actions. A petition was filed with the IACHR in 2000, and in the next five years another four petitions were lodged with the Surinamese government to halt the destruction of their territory (19). However, the State did not respond to the Saramaka’s appeals, leading the IACHR to refer the matter to the Inter-American Court for adjudication.

In deciding the Saramaka case in 2007, the Court delivered a ruling almost identical in nature to that later put forth in Kaliña and Lokono. However, the government of Suriname has roundly failed to implement the most important provisions of the 2007 judgment (20). As the deadlines for adherence to the judgment came and went, additional threats to the Saramaka emerged. Representatives reported further land incursions after 2007 as the government continued to issue mining and logging concessions, and quite incredibly, a permit for the construction of a tourist resort inside of a Saramaka village (21). Any hopes that the recently instituted Commissioner on Land Rights would address these pressing concerns have proved to be misplaced, as the priorities identified by the Commissioner failed to include any of the legislative changes needed to establish collective legal personality or security of land tenure for ITPs (22).

The outright refusal of the Surinamese government to respect the IACHR ruling and rights of the Saramaka, owing to a belief that conferring rights upon ITPs would be discriminatory to the rest of the population, represents a sharp rupture from the general trend towards greater recognition of ITPs throughout the Americas. Acceptance of the Surinamese government’s position would undermine the basis for minority rights worldwide. The Inter-American Court unequivocally rejected such arguments during its handling of the Saramaka case, and again in the latest Kaliña and Lokono case, but the government continues to expound variations of these legal fictions (23). Given the government’s position, it is likely that the Kaliña and Lokono will face similar challenges with securing meaningful action from the government.

The breakdown between the regional court rulings and their implementation points to an institutional weakness that exists within the Inter-American system—the absence of an effective enforcement mechanism. But it also speaks to the lack of political will to realize ITPs’ territorial rights at the national level. Denunciations from the UN’s Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (UNCERD) (24) and Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (25) have done little to compel Suriname to implement the Inter-American Court’s orders.

The Promise of REDD+?

An encouraging new leverage point may be Suriname’s recent interest in the World Bank’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) program. Under the terms of this scheme, which aims to promote the sustainable management of forests in developing countries, Suriname would receive technical assistance to diversify and restructure its economy along sustainable lines. If successful, it could lead to an incentivized payment system that rewards Suriname for averting forest degradation and increased carbon emissions in the course of its development (26).

Encouragingly, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has since been contracted as a delivery partner owing to the complexities of the project. The UNDP has outlined that it cannot participate in any initiative that violates international law, specifically calling attention to the Saramaka judgment as evidence that land tenure issues involving ITPs must be resolved if REDD+ is to be effectively implemented (27). A similar requirement has been expressed by the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) (28), the body charged with overseeing the project. This leadership from project partners make it clear that if Suriname wants to benefit from the program it must recognize the collective rights of ITPs.

In the immediate, challenges remain for the ITPs of Suriname. The Surinamese government has been clear in its presentations to the World Bank that it views all natural resources as state property (29). Even if the government changes its position actual implementation of legal recognition for ITPs’ rights will take years to achieve. For the foreseeable future, the Kaliña and Lokono remain vulnerable to the same encroachments upon their territory as experienced by the Saramaka since 2007. If concerted pressure by international financial and political institutions is not brought to bear upon Suriname to fulfill its responsibilities towards its most vulnerable citizens, communities like the Kaliña and Lokono will continue to be marginalized by a model of development that denies their self-determination—and endangers their very existence. Continued attention from international organizations, advocates, legal empowerment practitioners, and land rights defenders around the world is needed to ensure that the history of the Saramaka case is not repeated. Legal victories like that of the Kaliña and Lokono must be made real.

About the author: Dorian Martinez is a British researcher with an interest in indigenous rights to land and resources, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean. He has been volunteering on Namati’s CaseBase project since April 2015.

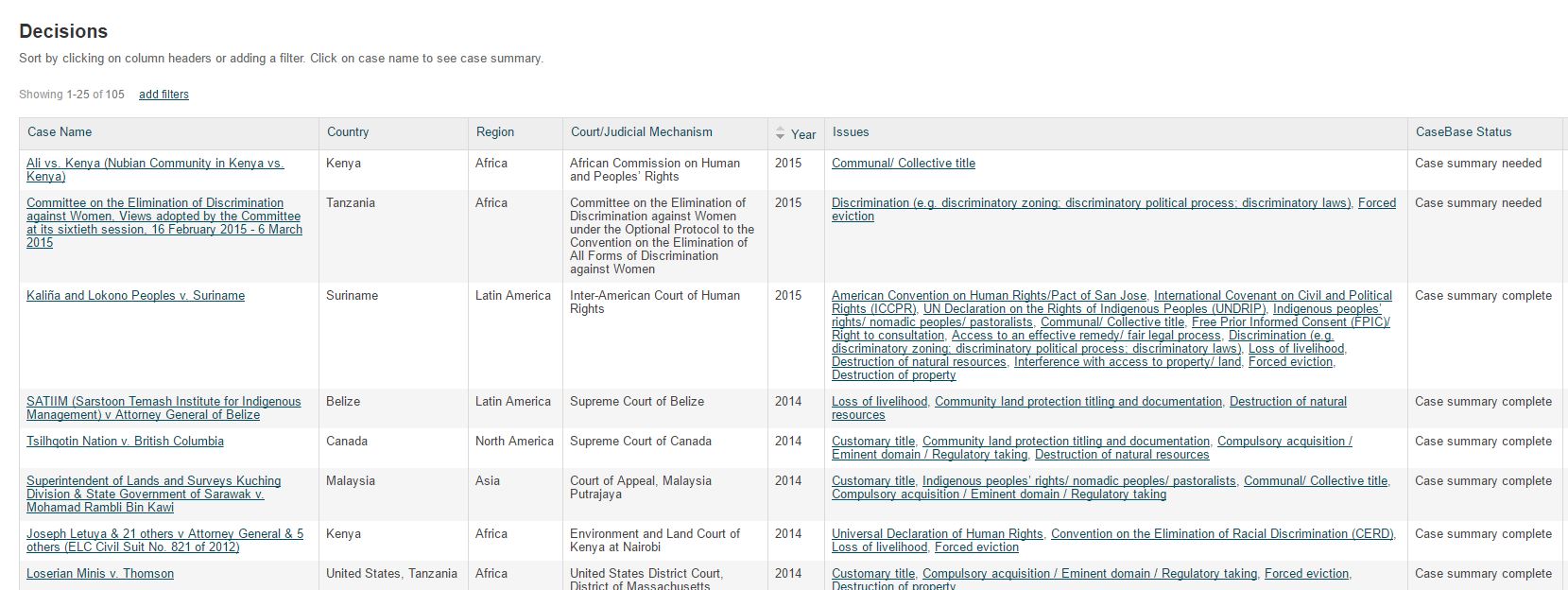

About Namati’s Community Land Rights CaseBase: Launched in 2015, CaseBase is the first global database of legal precedent on community land and resource rights. CaseBase is a tool to help communities, lawyers, and advocates to access and share case law and craft effective legal and advocacy strategies for defending community rights to land and natural resources.

Notes: