Staff: “What is the size of your community’s lands, would you say? How many days would it take you to walk around the outer boundary?”

Elder: “Oh, you could walk around it in two days.”

Staff: “Two days only?”

Elder: “Yes – I think so. But if we walk with you it will take longer – you are slower than us.”

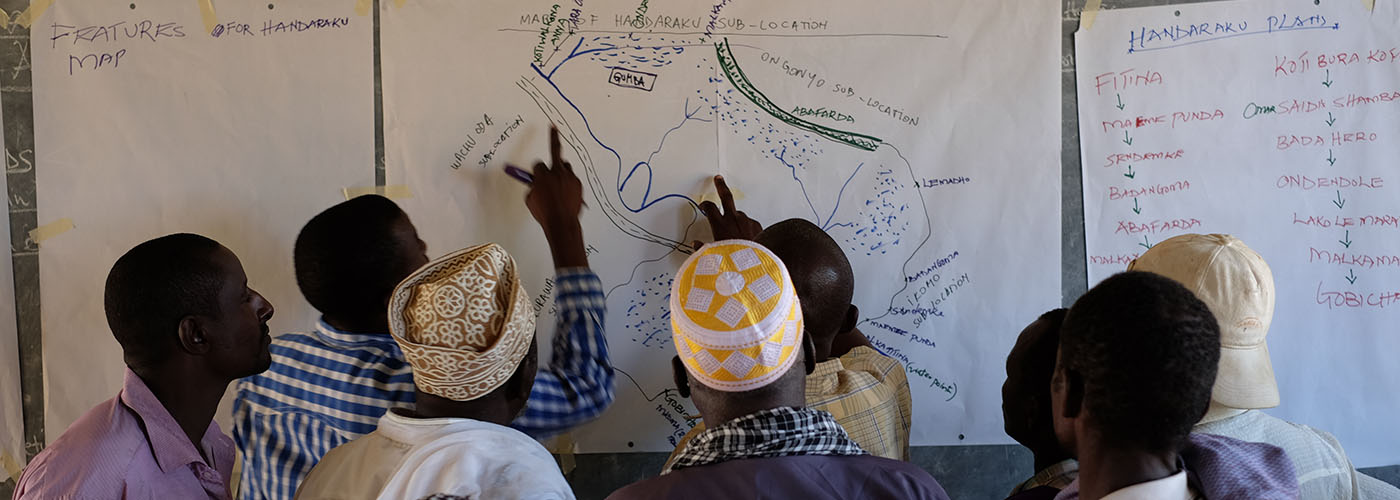

So began the planning of a pilot participatory mapping process in Kenya this February. Namati, the Kenya Land Alliance (KLA), and the communities of Chara and Handaraku in Tana River county are together discovering that community mapping is an art – and a messy one at that.

Even for experienced experts with professional equipment and ample resources, mapping is an extensive undertaking. Combine the technical challenges of mapping with a community-driven, empowerment-based approach and you have a task that should not be underestimated.

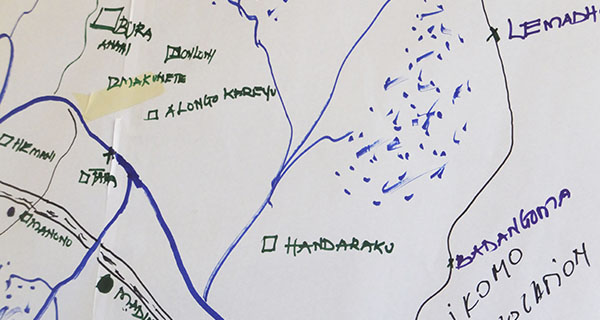

For the first years of Namati’s Community Land Protection program, the mapping component of the process relied upon simple ‘sketch-maps.’ To create a simple sketch-map, community members meet to discuss the spatial layout of their territory and draw it on a blank piece of paper. Sketch-maps can contain a great deal of information, including types and relative locations of natural resources and land use areas and major landmarks such as rivers, roads, or mountains. However, sketch-maps are also often unreliable because they are typically not ‘to scale’ (relative distances may not correspond the actual landscape) and they may lack key landmarks. In particular, sketch maps often miss or poorly represent features that communities find difficult to conceptualize and draw from a bird’s-eye-view perspective, such as coastlines or the shapes of forested or grassland areas.

Sketch map of Handaraku

Sketch-maps can be difficult to interpret – especially for people from outside the community, such as government or court officials. This limits their usefulness as a legal or technical record of a community’s lands. As a result, in many cases, communities would need to request or hire a licensed surveyor to visit their community to take the coordinates of their land if they wanted to apply for legal title or registration of their lands. Unfortunately, in many countries where our partners work licensed surveyors are difficult to access, which creates a barrier for communities that want to complete their land registration requirements.

Namati and partners realized there was a need to explore other tools and technologies that could improve the quality of communities’ maps.

Participatory mapping is currently a hot topic for many organizations working on land rights, social justice, and environmental conservation. Advancements in technology and the emergence of ‘open source’ software for mapping are making it easier than ever before for organizations, groups, and individuals to create spatial data. However, matching the goals and needs of a mapping project with appropriate techniques and tools requires careful evaluation and clear process design.

Namati and KLA set out to learn from the experts. We teamed up with the Nairobi-based mapping organization Spatial Collective (with funding support from the Omidyar Network) to learn about how to use GPS (Global Positioning System) technology to record coordinates with communities and how to then turn that data into maps. (Namati has also teamed up with another partner, Cadasta, to test additional tools including GeoODK and mobile phones in Kenya and Zambia this summer.)

Spatial Collective trained KLA Community Facilitators to use GPS

For three days in February, Spatial Collective trained staff from KLA and Namati on how to interpret satellite imagery and use hand-held GPS devices (we used the Garmin eTrek 20x) to record locations. We also learned how to view and work with the GPS data in open source mapping software called Quantum GIS. Then we all travelled to Tana River county in coastal Kenya to collaborate with two communities that had agreed to pilot the new mapping technology with us, Chara and Handaraku.

Chara and Handaraku have been working with KLA for over a year. They had completed their initial sketch maps and negotiated their boundaries with their neighboring communities. However, they wanted to improve upon the accuracy of their sketch maps and were eager to try new techniques. The Lands Department of the Tana River county government was also supportive of the pilot as a way to test a community-based mapping methodology to help resolve land disputes and reduce the workload on the county surveying staff.

KLA’s Community Facilitators and the communities’ selected representatives worked together to plan the logistics for how to collect the coordinates for the community boundaries and other key features that the communities wanted to map. After a day of planning routes, schedules, and supplies, we divided into four mapping teams, two for each community. Each team included a KLA Community Facilitator, a Namati or Spatial Collective advisor, a Community Land Rights Mobilizer, a local Chief or elder, and 2-3 other community representatives who knew the area or who had been selected to witness the data collection. Each team was equipped with a hand-held GPS, a log-sheet, a camera, a copy of the sketch map, water and snacks, and a vehicle.

Careful logistics planning was critical for the data collection

For two days, the teams diligently collected data – travelling by vehicle where possible, but also by motorbike, canoe, and on foot. The knowledgeable community representatives lead their teams across grazing lands, villages, forests and wildlife areas to reach the boundary locations that had been negotiated with neighbors, stopping to record features along the way. Each evening, we transferred and reviewed the data collected and watched as the blank map began to fill in with the points and tracks of the four teams.

Collecting boundary points and community features took us deep into the Tana River Delta

Even after only two days of supported learning and testing with Chara and Handaraku, many lessons were clear. First, we experienced challenges and delays that can come from gaps in logistics planning, especially when mapping large areas with multiple teams. Everything must be discussed and planned well in advance, from safety and scheduling down to footwear, snacks, and sun protection – in the words of Spatial Collective’s Primož Kovačič, participatory community mapping is “like a mini military operation!” We also realized the necessity of extensive community mobilization to ensure that everyone you encounter knows about what you are doing. Even then, as KLA’s Community Facilitators demonstrated, it is essential to be prepared with careful and clear explanations of the work when encountering people who have not heard about the mapping or who are critical or skeptical about it. There were no serious incidents on this pilot, but Spatial Collective and the Tana River county surveyor shared many stories about being chased out of communities by people opposed to, or afraid of, the idea of mapping.

Sketch maps proved challenging to navigate by

We also learned about the value of investing in sketch mapping techniques that would produce more detailed and accurate maps in advance of collecting coordinates. This would help to better anticipate logistics, terrain, and routes and to ensure that enough coordinates are recorded to accurately reflect the boundaries and community features. More detailed sketch maps can also allow mapping teams to identify features that can be digitized direct from satellite imagery, such as roads and rivers, and therefore do not need to be visited. Already in response to this learning, Namati and Cadasta are working to enhance the availability of quality satellite imagery that can be used for sketch-mapping through the free online tool FieldPapers.

After the data collection days, the communities of Chara and Handaraku were eager to see the fruits of their efforts. However, the data needed to be fully transferred, cleaned, and combined with satellite imagery in order to make the final maps. This meant that KLA, Namati, and Spatial Collective needed to leave the communities with the data, promising to return with draft maps for review.

To address community concerns about what would happen to the map data, and to reduce the power imbalances that come with technical processes, KLA and Namati decided to create a formal agreement with each community regarding the ownership and use of the mapping data. Namati and KLA created a Data Sharing Agreement template and discussed with both communities how they would like to share and control their mapping information. This put communities in control of their map data, how it could be used, and who it could be shared with and the formal agreement also strengthened the community members’ sense that they could hold KLA and Namati accountable if they felt that the terms was broken. After seeing the empowering effect of the Data Sharing Agreements, we are now adding this as a step to do before taking GPS coordinates in other communities. We anticipate that this will help to proactively address concerns about data use and security and encourage communities to ‘own’ the process of mapping.

The Land Rights Mobilizers of Chara and Handarku advised KLA and Namati on how to improve the community mapping process

Back in Nairobi, KLA staff and Namati’s David James Arach joined Spatial Collective in their office for 3 days of applied cartography – map making – using the open source mapping software Quantum GIS. KLA staff learned how to combine the GPS coordinates with satellite imagery and create digital map features by digitizing information from satellite imagery. Next, Chara and Handaraku will review draft maps and make additions or revisions and confirm the mapped boundaries with their neighboring communities. Once the maps are finalized by each community, they will submit them to the county government for official approval as a base map of the community’s territory – a major step towards greater tenure security and community land registration.

Mapping is exciting and powerful. It can create a visual, translatable record of a community’s territory that can be used to strengthen community’s legal rights to their lands. But it can also provoke intense conflict and fear, as boundaries that have never been recorded before are made clear and as information about a community never before shared beyond the local knowledge-holders is translated into a form that is harder to control and protect.

It is also the most technically demanding part of the community land protection process, and one that can easily be shaped – or limited – by the technology and technical capacity available rather than by the goals and needs of the process. Going forward, Namati and our partners are producing a series of practical resources and guides for how to plan for participatory community mapping in a practical, affordable, safe, goal-appropriate, and community-driven way. Stay tuned – we will be sharing those findings later this year!

Marena Brinkhurst is a Program Officer with Namati’s Community Land Protection Program and leads our new mapping initiatives.